Table of Contents

- 1 Common reasons why Adventists continue to keep the Sabbath:

- 1.1 Sabbath observance is one of the Ten Commandments:

- 1.2 Jesus kept the Sabbath:

- 1.3 The Sabbath was created in Eden before the Fall of mankind:

- 1.4 The Sabbath will be kept in the New Earth by all mankind:

- 1.5 The disciples of Jesus kept the Sabbath:

- 1.6 The Early Christian Church kept the Sabbath:

- 1.7 Historians on Sabbath Observance by Early Christians:

- 1.8 Early Attempts to Remove the Sabbath from Christianity:

- 1.9 Sabbath vs. Sunday:

- 1.9.1 Emperor Constantine (274-337 AD):

- 1.9.2 Gregory of Nyssa (335-394):

- 1.9.3 Spain – Council of Elvira (A.D.305):

- 1.9.4 Persia (335-375 AD):

- 1.9.5 John Chrysostom (349-407 AD):

- 1.9.6 The interpolater of Ignatius (4th Century):

- 1.9.7 Apollinaris Sidonius (430-489 AD):

- 1.9.8 Ulfilas (310-383 AD)

- 1.9.9 Athanasius (~366 AD):

- 1.9.10 Timotheus (381-385 AD):

- 1.9.11 Epiphanius (380 AD):

- 1.9.12 Sozomen (400-450 AD):

- 1.9.13 Socrates Scholasticus (380-440 AD):

- 1.9.14 Apostolic Constitutions (375-380 AD):

- 1.9.15 Didascalia (300s AD):

- 1.9.16 Eastern Orthodox Church:

- 1.9.17 6th-7th Century Scotland and Ireland:

- 1.9.18 8th Century India, China, and Persia:

- 1.9.19 10th Century Kurdistan:

- 1.9.20 11th Century Scotland:

- 1.9.21 12th Century Wales:

- 1.9.22 16th Century Germany:

- 1.10 Summary:

- 2 Why Don’t All Christians Observe the Sabbath?

- 2.1 The short story of Sabbath and the Early Church:

- 2.1.1 Sabbath first observed alongside Sunday:

- 2.1.2 Hadrian’s Anti-Jewish Laws suppress Sabbath observance:

- 2.1.3 Constantine’s Sunday Law enhanced Sunday observance:

- 2.1.4 Eusebius:

- 2.1.5 Ephraem Syrus:

- 2.1.6 Long decline of Sabbath observance:

- 2.1.7 Socrates and Sozomen:

- 2.1.8 Council of Laodicea (363–364 AD):

- 2.1.9 Third Synod of Orleans (538 AD):

- 2.1.10 Second Synod of Macon (585 AD):

- 2.1.11 King Guntram’s Decree (585 AD):

- 2.1.12 Walter W. Hyde:

- 2.1.13 Seventh-day Sabbath remnants:

- 2.1.14 Sunday as the new Sabbath:

- 2.2 The Catholic Argument:

- 2.3 The Orthodox Argument:

- 2.4 The Protestant Argument:

- 2.5 Common arguments against Sabbath observance:

- 2.5.1 No Sabbath before Sinai:

- 2.5.2 Colossians 2:

- 2.5.3 Acts 20:7

- 2.5.4 No Distinction Between any of the Old Testament Commandments:

- 2.5.5 Romans 14:5 and “The New Covenant”:

- 2.5.6 The New Covenant Based on Entirely New Laws of Grace:

- 2.5.7 Ephesians 6:1-3:

- 2.5.8 Nine of the Ten Commandments still Binding:

- 2.5.9 The Ten Commandments are Not Eternal:

- 2.5.10 The Ten Commandments are not “All Encompassing”:

- 2.5.11 The Ten Commandments are not Perfect:

- 2.5.12 The Sabbath Commandment is Ceremonial:

- 2.5.13 Jesus broke the Sabbath to undermine its authority:

- 2.5.14 Every day should be treated like a Sabbath:

- 2.5.15 Jesus Fulfilled All of the Laws:

- 2.5.16 Sabbath given only to the Jews:

- 2.5.17 Circumcision tied to the Sabbath Commandment:

- 2.5.18 Isreal not to make friends with other nations:

- 2.5.19 The Greeks have always hated Jewish laws and customs:

- 2.5.20 The Seventh-day Sabbath is ceremonial:

- 2.5.21 The Sabbath a Memorial of Isreal’s Deliverance from Slavery:

- 2.5.22 Creation week Sabbath as a “Prolepsis”:

- 2.5.23 The word “Sabbath” is not used in Genesis:

- 2.5.24 The Sabbath as a “Propitiation”:

- 2.5.25 The Sabbath for Human Beings; not “Subhuman” Gentiles:

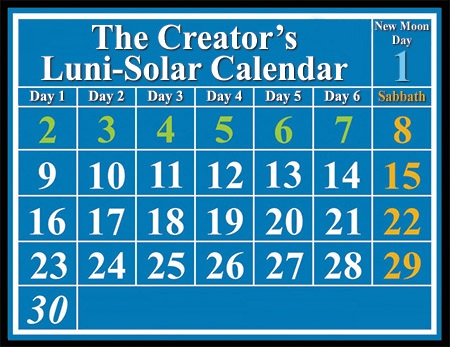

- 2.5.26 The Lunar Sabbath (The Sabbath is not Saturday):

- 2.5.27 Ignatius in his Epistle to the Magnesians (107 AD):

- 2.5.28 Ignatius in his Epistle to the Trallians:

- 2.5.29 Epistle of Barnabas (140-150 AD):

- 2.5.30 Review of “Lying for God” by Brendon Knudson:

- 2.5.31 Review by Kerry Wynne (principle author of Lying for God):

- 2.5.32 Anti-Sabbatarian views of Dr. Clinton Baldwin:

- 2.1 The short story of Sabbath and the Early Church:

- 3 Debate on the Sabbath and Ten Commandments:

- 4 Summary Power Point Presentation:

Last update: May 15, 2017

Most Christian denominations today worship on Sunday, or the first day of the week, rather than on the Sabbath, or the seventh day of the week. Yet, Seventh-day Adventists and other Sabbatarians continue to observe the Sabbath as a “holy day” – along with practicing Jews. Why? What is so important about Sabbath observance for Seventh-day Adventists? And, is it even biblical?

Most Christian denominations today worship on Sunday, or the first day of the week, rather than on the Sabbath, or the seventh day of the week. Yet, Seventh-day Adventists and other Sabbatarians continue to observe the Sabbath as a “holy day” – along with practicing Jews. Why? What is so important about Sabbath observance for Seventh-day Adventists? And, is it even biblical?

Common reasons why Adventists continue to keep the Sabbath:

Sabbath observance is one of the Ten Commandments:

Perhaps the primary reason why Adventists continue to observe the 7th-day Sabbath is that it is one of the Ten Commandments written by God’s own finger in stone (Exodus 20:1-17 and Deuteronomy 5:12-15). God does very little writing with His own finger – and only once in stone (Deuteronomy 5:22). This suggests the permanent nature of the Ten Commandments as a written expression of the Royal Law of Love toward God and toward one’s neighbor (James 2:8; Galatians 5:14; Matthew 22:37-40). James, for examples, specifically links up the Royal Law of Love with the Ten Commandments as follows:

If you really keep the royal law found in Scripture, “Love your neighbor as yourself,” you are doing right. But if you show favoritism, you sin and are convicted by the law as lawbreakers. For whoever keeps the whole law and yet stumbles at just one point is guilty of breaking all of it. For he who said, “You shall not commit adultery,” also said, “You shall not murder.” If you do not commit adultery but do commit murder, you have become a lawbreaker. Speak and act as those who are going to be judged by the law that gives freedom, because judgment without mercy will be shown to anyone who has not been merciful. Mercy triumphs over judgment.

James 2:8-13

Here James is simply repeating what Jesus said about the Law being based on the underlying Law of Love – a fundamental principle upon which all of God’s laws are based (Matthew 22:37-40).

Added to this is the fact that only the Decalogue, written by the Finger of God, was placed inside of the Ark of the Covenant. All of the other Mosaic laws were placed on the outside of the Ark “as a witness against you” (Deuteronomy 31:26).

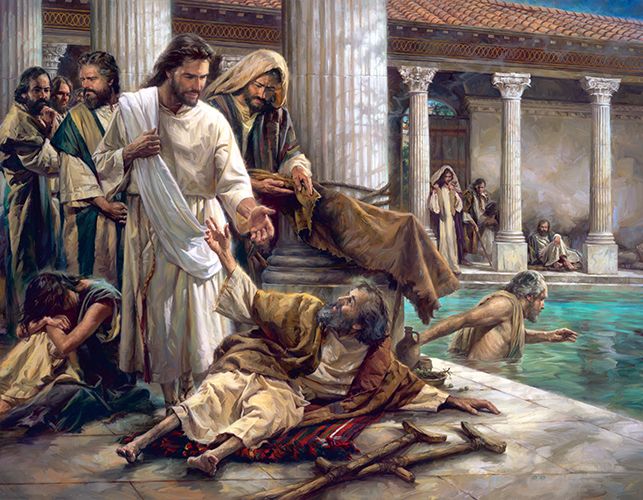

Jesus kept the Sabbath:

During His lifetime:

Another common reason cited for Sabbath observance for the Christian is that Jesus kept the Sabbath. It was His custom to worship in the local synagogue on the Sabbath day (Luke 4:16).

And, when accused of breaking the Sabbath, He cited Jewish law that allowed for the breaking of the Sabbath in certain situations – to include a direct service to God (Matthew 12:5) or to relieve the suffering of man or even beast (Luke 13:15; Luke 14:5; Matthew 12:11). Jesus concluded with the argument: “How much more valuable is a man than a sheep! Therefore it is lawful to do good on the Sabbath.” (Matthew 12:12).

Of course, since this was in fact right in line with Jewish law, there wasn’t much that could be said to contradict this conclusion on the matter. However, just to drive His point home a bit more, Jesus added, “The Sabbath was made for man, not man for the Sabbath.” (Mark 2:27). Here Jesus claimed that He had Himself originally created the Sabbath to be a blessing for all of mankind (“anthropos” in the original Greek text) – not just for the Jews. Also, as the Creator of the Sabbath, Jesus claimed to be able to appropriately define the meaning of the day as the “Lord of the Sabbath” (Mark 2:28). It is in this way that Jesus could accurately claim that He truly kept all of the Laws of God perfectly as God actually intended them to be kept (John 15:10).

Even during His own time in the grave, Jesus paid respect to the Sabbath by staying in the tomb over the Sabbath hours. The same is true for His followers during this time. “Then they went home and prepared spices and perfumes, but they rested on the Sabbath in obedience to the commandment.” (Luke 23:56). This clearly indicates that neither Jesus nor His followers saw any change in Sabbath sacredness following the crucifixion.

Would continue to be kept in the future by the Christians:

Beyond this, Jesus predicted that future Christians would continue their observance of the Sabbath after His time – explaining that His followers should pray that their future flight from the Roman armies, armies that would destroy Jerusalem (some 40 years later in 70 AD), not take place in the winter or on the Sabbath day (Matthew 24:20). The usual counter to this argument is that Jesus said this for practical reasons, not because His disciples would be keeping the Sabbath as a holy day, but so that they could more effectively flee if their flight were not on a Sabbath day (given that the gates of the cities would be closed on the Sabbath).

Beyond this, Jesus predicted that future Christians would continue their observance of the Sabbath after His time – explaining that His followers should pray that their future flight from the Roman armies, armies that would destroy Jerusalem (some 40 years later in 70 AD), not take place in the winter or on the Sabbath day (Matthew 24:20). The usual counter to this argument is that Jesus said this for practical reasons, not because His disciples would be keeping the Sabbath as a holy day, but so that they could more effectively flee if their flight were not on a Sabbath day (given that the gates of the cities would be closed on the Sabbath).

The problem with this argument, however, is that, according to Josephus, everything was left wide open for the Christians to flee from Jerusalem. Even the gates of the temple itself were miraculously opened as a sign of God’s departure (Link). Also, the Roman armies initially retreated and the Jewish soldiers chased after them – leaving the city and the countryside undefended and wide open for the Christians to escape (Link). Numerous historians have commented on this miraculous situation:

The problem with this argument, however, is that, according to Josephus, everything was left wide open for the Christians to flee from Jerusalem. Even the gates of the temple itself were miraculously opened as a sign of God’s departure (Link). Also, the Roman armies initially retreated and the Jewish soldiers chased after them – leaving the city and the countryside undefended and wide open for the Christians to escape (Link). Numerous historians have commented on this miraculous situation:

“This counsel [of Matthew 24:16] was remembered and wisely followed by the Christians afterwards. Eusebius and Epiphanius say, that at this juncture, after Cestius Gallus had raised the siege, and Vespasian was approaching with his army, all who believed in Christ left Jerusalem and fled to Pella, and other places beyond the river Jordan; and so they all marvellously escaped the general shipwreck of their country: not one of them perished (see Matthew 24:13).”

“This counsel [of Matthew 24:16] was remembered and wisely followed by the Christians afterwards. Eusebius and Epiphanius say, that at this juncture, after Cestius Gallus had raised the siege, and Vespasian was approaching with his army, all who believed in Christ left Jerusalem and fled to Pella, and other places beyond the river Jordan; and so they all marvellously escaped the general shipwreck of their country: not one of them perished (see Matthew 24:13).”

Adam Clarke (1837) Commentary On Matthew 24

“How exactly the several passages of story in Josephus agree with these predictions will easily be discerned by comparing them, particularly that which belongs to this place of their flying to the mountains. For when Gallus besieged Jerusalem, and without any visible cause, on a sudden raised the siege, what an act of God’s special providence was this, thus to order it, that the believers of Christian Jews being warned by this siege, and let loose (set at liberty again) might fly to the mountains, that is, get out of Judea to some other place! Which that they did accordingly appears by this, that when Titus came some months after and besieged the city, there was not one Christian remaining in it”

“How exactly the several passages of story in Josephus agree with these predictions will easily be discerned by comparing them, particularly that which belongs to this place of their flying to the mountains. For when Gallus besieged Jerusalem, and without any visible cause, on a sudden raised the siege, what an act of God’s special providence was this, thus to order it, that the believers of Christian Jews being warned by this siege, and let loose (set at liberty again) might fly to the mountains, that is, get out of Judea to some other place! Which that they did accordingly appears by this, that when Titus came some months after and besieged the city, there was not one Christian remaining in it”

Henry Hammond (1659), vol. 3, p. 160

“It is a remarkable but historical fact that Cestius Gallus, the Roman general, for some unknown reason, retired when they first marched against the city, suspended the siege, ceased the attack and withdrew his armies for an interval of time after the Romans had occupied the temple, thus giving every believing Jew the opportunity to obey the Lord’s instruction to flee the city. Josephus the eyewitness, himself an unbeliever, chronicles this fact, and admitted his inability to account for the cessation of the fighting at this time, after a siege had begun. Can we account for it? We can. The Lord was fighting against Jerusalem Zechariah 14:2: ‘For I will gather all nations against Jerusalem to battle; and the city shall be taken, and the houses rifled, and the women ravished; and half of the city shall go forth into captivity, and the residue of the people shall not be cut off from the city: The Lord was besieging that city. God was bringing these things to pass against the Jewish state and nation. Therefore, the opportunity was offered for the disciples to escape the siege, as Jesus had forewarned, and the disciples took it. So said Daniel; so said Jesus; so said Luke, so said Josephus”

“It is a remarkable but historical fact that Cestius Gallus, the Roman general, for some unknown reason, retired when they first marched against the city, suspended the siege, ceased the attack and withdrew his armies for an interval of time after the Romans had occupied the temple, thus giving every believing Jew the opportunity to obey the Lord’s instruction to flee the city. Josephus the eyewitness, himself an unbeliever, chronicles this fact, and admitted his inability to account for the cessation of the fighting at this time, after a siege had begun. Can we account for it? We can. The Lord was fighting against Jerusalem Zechariah 14:2: ‘For I will gather all nations against Jerusalem to battle; and the city shall be taken, and the houses rifled, and the women ravished; and half of the city shall go forth into captivity, and the residue of the people shall not be cut off from the city: The Lord was besieging that city. God was bringing these things to pass against the Jewish state and nation. Therefore, the opportunity was offered for the disciples to escape the siege, as Jesus had forewarned, and the disciples took it. So said Daniel; so said Jesus; so said Luke, so said Josephus”

Foy Wallace (1966), The Book of Revelation, p. 352

Clearly then, there would have been no physical issue regarding Christian escape if it had been a Sabbath day. So, this doesn’t seem to be the reason why Jesus reminded the Christians to pray that their flight not take place on the Sabbath day. Rather, fleeing on the Sabbath day would be less desirable because it would mean that they wouldn’t be able to actually enjoy the Sabbath if they had to flee on that day.

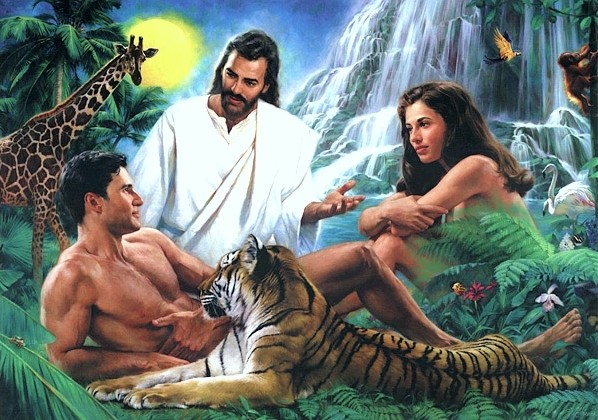

The Sabbath was created in Eden before the Fall of mankind:

At the end of the creation week described in Genesis, “God blessed the seventh day and made it holy, because on it he rested from all the work of creating that he had done.” (Genesis 2:3). Later, Jesus explain that the “Sabbath was made for man (literally translated “the man” or “Adam”).” (Mark 2:27)

At the end of the creation week described in Genesis, “God blessed the seventh day and made it holy, because on it he rested from all the work of creating that he had done.” (Genesis 2:3). Later, Jesus explain that the “Sabbath was made for man (literally translated “the man” or “Adam”).” (Mark 2:27)

It seems, then, that Jesus originally created the Sabbath day as a special social day of rest from the usual activities of life to have an entire day to spend especially with God. This was a gift from God for all of humankind – originally given back in Eden before sin had even entered the world. Why then would such a gift be discarded by the Christian?

The Sabbath will be kept in the New Earth by all mankind:

The Sabbath will be kept in the New Earth by all mankind:

“As the new heavens and new earth that I make will endure before me,” declares the LORD, “so will your name and descendants endure. From one New Moon to another and from one Sabbath to another, all mankind will come and bow down before me,” says the LORD. (Isaiah 66:22-23)

The disciples of Jesus kept the Sabbath:

It seems as though the disciples of Jesus continued to keep the Sabbath, as Jesus kept it, even after His death and resurrection. There are many mentions of the disciples and other followers of Jesus coming together to worship on the Sabbath day – as was their custom (Acts 17:2). The Book of Acts alone gives a record of Paul holding eighty-four worship meetings upon that day (Acts 13:14, 44; 16:13; 17:2; 18:4-11). In fact, the best interpretation of John’s phrase “the Lord’s Day” is that John was talking about the Sabbath (Revelation 1:10). After all, up until that point in the history of the early Christian Church, only the Sabbath had ever been referred to as “the Lord’s Day” (Mark 2:28 and Isaiah 58:13). This is right in line with the fact that the Christians continued to worship in the temple and in their synagogues, as they had always done (Acts 3:1). No significant changes to their customs of worship are described in the Bible.

It seems as though the disciples of Jesus continued to keep the Sabbath, as Jesus kept it, even after His death and resurrection. There are many mentions of the disciples and other followers of Jesus coming together to worship on the Sabbath day – as was their custom (Acts 17:2). The Book of Acts alone gives a record of Paul holding eighty-four worship meetings upon that day (Acts 13:14, 44; 16:13; 17:2; 18:4-11). In fact, the best interpretation of John’s phrase “the Lord’s Day” is that John was talking about the Sabbath (Revelation 1:10). After all, up until that point in the history of the early Christian Church, only the Sabbath had ever been referred to as “the Lord’s Day” (Mark 2:28 and Isaiah 58:13). This is right in line with the fact that the Christians continued to worship in the temple and in their synagogues, as they had always done (Acts 3:1). No significant changes to their customs of worship are described in the Bible.

There was also never any dispute between the Christians and the Jews about the Sabbath day. This is good evidence that the early Christians still observed the same day that the Jews did.

The Early Christian Church kept the Sabbath:

Historians are in general agreement that the early Christians, Jews and gentiles, continued to observe the Sabbath as a holy day – as well as Sunday in celebration of the resurrection. This is despite the fact that a number of early church fathers favored Sunday observance over the Sabbath – especially starting in the second century during the anti-Jewish laws of Emperor Hadrian.

Philo of Alexandria (20 BC – 50 AD):

Philo, who was born and raised in Alexandria, Egypt. He noted that the seventh day was to be a festival, “not of this or that city, but of the universe” – not to be reserved for the Jews only:

The seventh day is the completion of creation, “for it is the festival, not of a single city or country, but of the universe, and it alone strictly deserves to be called ‘public’ as belonging to all people and the birthday of the world.”

“Every seventh day is sacred, which is called by the Hebrews the sabbath; and the seventh month in every year has the greatest of the festivals allotted to it, so that very naturally the seventh year also has a share of the veneration paid to this number, and receives especial honour.”

“The fourth commandment has reference to the sacred seventh day, that it may be passed in a sacred and holy manner. Now some states keep the holy festival only once in the month, counting from the new moon, as a day sacred to God; but the nation of the Jews keep every seventh day regularly, after each interval of six days; and there is an account of events recorded in the history of the creation of the world, comprising a sufficient relation of the cause of this ordinance; for the sacred historian says, that the world was created in six days, and that on the seventh day God desisted from his works, and began to contemplate what he had so beautifully created; therefore, he commanded the beings also who were destined to live in this state, to imitate God in this particular also, as well as in all others, applying themselves to their works for six days, but desisting from them and philosophising on the seventh day, and devoting their leisure to the contemplation of the things of nature, and considering whether in the preceding six days they have done anything which has not been holy, bringing their conduct before the judgment-seat of the soul, and subjecting it to a scrutiny, and making themselves give an account of all the things which they have said or done; the laws sitting by as assessors and joint inquirers, in order to the correcting of such errors as have been committed through carelessness, and to the guarding against any similar offences being hereafter repeated.”

Polycarp of Smyrna (69-155 AD):

Polycarp personally knew the Apostle John, and was his disciple. All of his life he was devoted to the teachings of John and the other Apostles and was considered to be a Nazarene. The 15th-century Jewish historian, sometimes called Rabbi Ifaac wrote:

Polycarp personally knew the Apostle John, and was his disciple. All of his life he was devoted to the teachings of John and the other Apostles and was considered to be a Nazarene. The 15th-century Jewish historian, sometimes called Rabbi Ifaac wrote:

“Polycarp…Born late in the reign of Nero, he became a Nazarene.”

Hoffman , David. Chronicles from Cartaphilus: The Wandering Jew. Published by , 1853. Original from the University of Michigan. Digitized Sep 7, 2007, p. 636

The Nazarenes:

Being a Nazarene meant, of course, that Polycarp continued to observe the Sabbath as a holy day of worship – as did the Apostle John before him since Polycarp was John’s disciple.

As late as the eleventh century, Cardinal Humbert of Mourmoutiers still referred to the Nazarene sect as a Sabbath-keeping Christian body existing at that time (Strong (1874), Cyclopedia, I, New York, p. 660). Modern scholars believe it is the Pasagini or Pasagians who are referenced by Cardinal Humbert, suggesting the Nazarene sect existed well into the eleventh century and beyond (from the Catholic writings of Bonacursus entitled “Against the Heretics“). It is believed that Gregorius of Bergamo, about 1250 AD, also wrote concerning the Nazarenes as the Pasagians.

The argument by some that the Nazarenes followed the floating “Lunar Sabbath” is based largely on John Keyser’s book, “From Sabbath to Saturday“ where a statement by Clement of Alexandria (150-215 AD) is referenced as follows:

“Neither worship as the Jews; for they, thinking that they only know God, do not know Him, adoring as they do angels and archangels, the month and the moon. And if the moon be not visible, they do not hold the Sabbath, which is called the first; nor do they hold the new moon, nor the feast of unleavened bread, nor the feast, nor the great day.” (Stromata, Chap. 5)

Lunar Sabbatarians commonly interpret this statement as follows:

This clearly indicates that at this time the weekly Sabbath was still dictated by the moon’s course (Link).

Well, not quite. Certainly, this passage does not trump the numerous statements from many authors concerning the regular weekly cycle of seven fixed days followed by the early Christians (including the Nazarenes) – along with a fixed Sabbath day every 7th day. Therefore, what Clement is most likely talking about here is one of the annual sabbaths – like the “Feast of Trumpets” (which happens to fall on “the first” day of the month of Tishrei).

For a more detailed discussion of the whole notion of a “Lunar Sabbath” see: Link

The Minim:

The same appears to be true of those who followed the teachings of the Apostle Paul – including the gentile Nazarenes up into the fourth and fifth centuries. They were sometimes derisively referred to as “Minim” by some of the Jews:

“In fact some Minim of gentile stock, following St. Paul, taught that the Law had been abolished with the exception of the Decalogue…”

Bagatti (Catholic Scholar). The Church from the Circumcision, p. 108

Irenaeus on Polycarp:

This devotion to the teaching of the Apostles was carefully noted by those around him and by those who came after. For example, Irenaeus, a contemporary of Polycarp (130-220 AD), spoke of Polycarp as follows:

But Polycarp also was not only instructed by apostles, and conversed with many who had seen Christ, but was also, by apostles in Asia, appointed bishop of the Church in Smyrna…always taught the things which he had learned from the apostles, and which the Church has handed down, and which alone are true. To these things all the Asiatic Churches testify, as do also those men who have succeeded Polycarp down to the present time

Irenaeus. Adversus Haeres. Book III, Chapter 4, Verse 3 and Chapter 3, Verse 4.

It is also interesting to note that Irenaeus and Eusebius both record how the Apostles Philip and John, as well as faithful church leaders and martyrs such as Polycarp and Melito, kept the Passover on the 14th of Nisan in accordance with the gospel and would not deviate from it.

Besides observing the Passover exactly on the 14th of Nisan, not always on the Sunday following, Polycarp also observed the Sabbath – as did the Nazarenes in general. Irenaeus, on the other hand, was known as a “peacemaker” and so adopted weekly Sunday observance as well as Easter Sunday observance (not usually on the 14th of Nisan). He also downplayed Sabbath observance, giving it a metaphysical meaning similar to the Gnostics – despite the influence of Polycarp.

Roman supporters ultimately did largely eliminate the Christian observance of the Passover on the 14th of Nisan – by the decree of the pagan Emperor Constantine in 325 AD.

In any case, while Irenaeus commended Polycarp for blasting the “heretic” Marcion (who tried to do away with the Old Testament, the law, and the Sabbath), he apparently did not think that changing the date of the Passover to Sunday (as some Roman bishops did) or the day of worship to Sunday (as Justin advocated) was heretical.

The account of Polycarp’s death at the stake also appears to cite Sabbath observance by his followers. According to the letter “The Martyrdom of Polycarp” by the Smyrnaeans:

“On the day of the preparation, at the hour of dinner, there came out pursuers and horsemen” and Polycarp was killed “on the day of the great Sabbath at the eighth hour.”

The encyclical epistle of the church at Smyrna, The Martyrdom of Polycarp, Bishop of Smyrna, Verses 7.1 & 8.1. Charles H. Hoole’s 1885 translation

Note: The margin says, “The great Sabbath is that before the passover.”

The use of these two expressions (“day of the preparation” and “the day of the great Sabbath”) strongly indicates that those in Polycarp’s area were still keeping the Sabbath as well as Holy Days, like the Passover, in the latter portion of the second century. Otherwise, since Asia Minor (including Smyrna) was a Gentile area, the terms “preparation day”, which was generally used in reference to the Friday preceding the weekly Sabbath day (since food preparation could be done on the annual sabbaths, but not on the weekly Sabbath), and “great Sabbath” would not have been relevant.

Vita Polycarpi (3rd to early 4th century):

This work is attributed to Pionius and is dated anywhere from the 3rd to the early 4th century A.D. Many historians view the Vita Polycarpi as a book of legends and fantastic supernaturalism, quoting non-existent documents, and not of any real historical value beyond what was taking place during the 3rd or 4th centuries. However, many historians view this document as having some historical value, such as in its descriptions of the life and liturgy of the 3rd-century church in Smyrna – as well as Christian interactions with the Jews and pagans. Specifically relevant to this discussion, the Christian community in this region of Smyrna is specifically described, in the Vita Polycarpi, as keeping the Saturday Sabbath in the same manner the Jews – and gathering for Biblical instruction and to celebrate Sabbath as a feast day with their brethren.

Polycrates of Ephesus (125-196 AD):

In the closing decades of the second century, Polycrates, a faithful church leader who had been personally trained by Polycarp, took over a leadership position (and was eventually crucified). He remained prominent Christian leader who was faithful to the example of the Apostles of the Jerusalem Church. Polycrates taught the true Gospel of the literal establishment of the Kingdom of God on earth, the unconscious state of the dead awaiting the resurrection, and the importance of keeping God’s Law.

In the closing decades of the second century, Polycrates, a faithful church leader who had been personally trained by Polycarp, took over a leadership position (and was eventually crucified). He remained prominent Christian leader who was faithful to the example of the Apostles of the Jerusalem Church. Polycrates taught the true Gospel of the literal establishment of the Kingdom of God on earth, the unconscious state of the dead awaiting the resurrection, and the importance of keeping God’s Law.

Toward the end of the second century, Victor, bishop of Rome, had begun labeling Polycrates and those who followed his teachings as heretics—sources of discord and schism in the church. Polycrates remained faithful despite increasing pressure and isolation as well as persecution and hostility from fellow Christians as well as the surrounding pagan society.

Theophilus, Bishop of Antioch (120-190 AD):

And on the sixth day God finished His works which He made, and rested on the seventh day from all His works which He made. And God blessed the seventh day, and sanctified it; because in it He rested from all His works which God began to create…Moreover, [they spoke] concerning the seventh day, which all men acknowledge; but the most know not that what among the Hebrews is called the “Sabbath,” is translated into Greek the “Seventh” (ebdomas), a name which is adopted by every nation, although they know not the reason of the appellation.

Theophilus of Antioch. To Autolycus, Book 2, Chapters XI, XII. Translated by Marcus Dods, A.M. Excerpted from Ante-Nicene Fathers, Volume 2. Edited by Alexander Roberts & James Donaldson. American Edition, 1885. Online Edition Copyright © 2004 by K. Knight

In the fifteenth chapter of this book, Theophilus compares those who “keep the law and commandments of God” to the fixed stars, while the “wandering stars” are “a type of the men who have who wandered from God, abandoning his law and commandments.”

In short, Theophilus bears testimony to the validity and binding nature of the commandments of the Decalogue, including the Sabbath, and says not one word concerning the observance of Sunday or the “Lord’s Day” as a holy day.

Historians on Sabbath Observance by Early Christians:

Edward Brerewood (1565-1613):

“It is certain that the ancient Sabbath did remain and was observed (together with the celebration of the Lord’s day) by the Christians of the East Church, above three hundred years after our Saviour’s death.”

A learned treatise of the Sabbath, written by Mr Edward Brerewood professor in Gresham Colledge, London. (1631)

T. H. Morer (1701):

“The primitive Christians had a great veneration for the Sabbath, and spent the day in devotion and sermons. And it is not to be doubted but they derived this practice from the Apostles themselves, as appears by several scriptures to the purpose.”

Dr. T. M. Morer, Dialogues on the Lord’s Day, p. 189. London: 1701

Jeremy Taylor (1613-1667):

“The primitive Christians did keep the Sabbath of the Jews;…therefore the Christians, for a long time together, did keep their conventions upon the Sabbath, in which some portions of the law were read: and this continued till the time of the Laodicean council.”

“The Whole Works” of Rev. Jeremy Taylor, Vol. IX, p. 416 (R. Heber’s Edition, Vol XII, p. 416).

Dr. Theodor Zahn (1838-1933):

“[The early Christians] observed the Sabbath in the most conscientious manner: otherwise, they would have been stoned. Instead of this, we learn from the book of the Acts that at times they were highly respected even by that part of their own nation that remained in unbelief….

That the observance of Sunday commenced among them would be a supposition which would have no seeming ground for it, and all probability against it….

The Sabbath was a strong tie which united them with the life of the whole people, and in keeping the Sabbath holy, they followed not only the example, but also the command of Jesus.

Geschichte des Sonntags, pp. 13, 14.

Lutheran Bishop Grimelund of Norway (1912-1896):

“The early Christians were of Jewish descent, and the first Christian church in Jerusalem was a Jewish- Christian church. It conformed, as could be expected, to the Jewish law and Sabbath-custom; it had no express instruction from the Lord to do otherwise…

But, one could reason, that for all this it does not follow that one should give up and forsake the ‘Sabbath’ which God Himself has commanded, nor that we should transfer this to another day of the week, even if that is such a memorable day. To do this would require an equally definite command from God, whereby the former command is abolished, but where can we find such a command? It is true, such a command is not to be found.”

“Sondagens Historie,” p. 13-18. Christiania, Norway: Den norske Lutherstiftelses Forlag, 1886.

Johann Gieseler (1792-1854):

The well-known Protestant church historian, Johann Gieseler, explains the situation as follows:

“While the Jewish Christians of Palestine, who kept the whole Jewish law, celebrated of course all the Jewish festivals, the heathen converts observed only the Sabbath, and, in remembrance of the closing scenes of our Saviour’s life, the Passover, though without the Jewish superstitions. Besides these, the Sunday, as the day of our Saviour’s resurrection, was devoted to religious worship”

Church History, Apostolic Age to A.D. 70, Section 29. See also: A Compendium of Ecclesiastical History,” Vol. I, chap. 2, see. 30, p. 92. Edinburgh: 1846.

Peter Heylyn (1599-1662):

And, during the first few hundred centuries, “Sabbath keeping was the practice generally of the Easterne Churches; and some churches of the West… For in the Church of Millaine [Milan]; … it seemes the Saturday was held in a farre esteeme … Not that the Easterne Churches, or any of the rest which observed that day were inclined to Iudaisme [Judaism]; but that they came together on the Sabbath day, to worship Iesus [Jesus] Christ the Lord of the Sabbath.”

And, during the first few hundred centuries, “Sabbath keeping was the practice generally of the Easterne Churches; and some churches of the West… For in the Church of Millaine [Milan]; … it seemes the Saturday was held in a farre esteeme … Not that the Easterne Churches, or any of the rest which observed that day were inclined to Iudaisme [Judaism]; but that they came together on the Sabbath day, to worship Iesus [Jesus] Christ the Lord of the Sabbath.”

Augustine of Hippo, a devout Sunday keeper, attested that the Sabbath was observed in the greater part of the Christian world (Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers, First Series, Vol. 1, pp. 353-354) and deplored the fact that in two neighbouring Churches in Africa, one observed the seventh day Sabbath, while another fasted on it.

Dr. Peter Heylyn, History of the Sabbath, London 1636, Part 2, para. 5, pp. 73-74, 416) original spelling retained)

Moses B. Stuart (1780-1852):

Professor Stewart, in speaking of the history of the Christian Church during the period from Emperor Constantine to the Council of Laodicea, says:

“The practice of it [the keeping of the Sabbath] was continued by Christians who were jealous for the honor of the Mosaic law, and finally became, as we have seen, predominant throughout Christendom. It was supposed at length that the fourth commandment did require the observance of the seventh-day Sabbath (not merely a seventh part of time). And reasoning as Christians of the present day are wont to do, viz., that all which belonged to the ten commandments was immutable and perpetual, the churches in general came gradually to regard the seventh day Sabbath as altogether sacred.”

Appendix to Gurney’s History, etc., of the Sabbath, pp. 115, 116.

So, after Constantine’s time, there seems to have been in a measure a revival of interest in, and reverence for, the Sabbath in the minds of most Christians throughout the Christian world – especially in the Eastern churches, where the influence of the Western Roman Church was less powerful.

Early Attempts to Remove the Sabbath from Christianity:

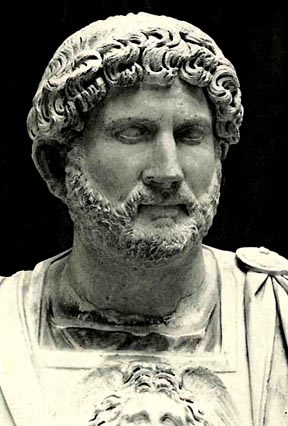

Hadrian (76-138 AD):

It is well documented that the early Christian church continued to keep the Sabbath throughout Christendom for a very long time. However, in Rome and Alexandria Sabbath observance first started to wane in the early second century. Under Vespasian (69-79 AD) both the Sanhedrin and the high priesthood were abolished, and under Hadrian, the practice of the Jewish religion (particularly Sabbathkeeping) was outlawed (around 135 AD). There was, in fact, a growing sentiment against anything resembling Jewishness during this time that was widespread – to include the Christian world as well as the pagan world.

It is well documented that the early Christian church continued to keep the Sabbath throughout Christendom for a very long time. However, in Rome and Alexandria Sabbath observance first started to wane in the early second century. Under Vespasian (69-79 AD) both the Sanhedrin and the high priesthood were abolished, and under Hadrian, the practice of the Jewish religion (particularly Sabbathkeeping) was outlawed (around 135 AD). There was, in fact, a growing sentiment against anything resembling Jewishness during this time that was widespread – to include the Christian world as well as the pagan world.

Writers such as Seneca (65 AD), Persius (34-62 AD), Petronius (66 AD), Quintilian (35-100 AD), Martial (40-104 AD), Plutarch (46 AD), Juvenal (125 AD), and Tacitus (55-120 AD), who lived in Rome for most of their professional lives, reviled the Jews racially and culturally. Particularly were the Jewish customs of Sabbathkeeping and circumcision contemptuously derided as examples of degrading superstitions.

Clearly then, Hadrian’s laws were not targeted at Christians, per se, but against the Jews in particular – largely because of the very bloody and costly Jewish revolts. Jerusalem was completely destroyed and then rebuilt as a Roman city with Roman temples. Jews were barred from even entering this city – while Christians were still allowed to enter. The Christians themselves largely got around the anti-Sabbath laws by “doing good deeds” and being generally active on the Sabbath – citing the activity of Jesus Himself on the Sabbath and how doing such activities for God was “lawful” to do on the Sabbath – as Jesus Himself point out. Fairly quickly, however, the leadership of the Christian churches, especially in the west, saw the expediency of viewing Sabbath observance in a more and more spiritual sense rather than in the literal sense that it had previously been observed.

Research has shown that during the second and third centuries various prominent leaders of the Christian communities endeavored, by being busy doing “divine work” on the Sabbath and allegorizing the meaning of the Sabbath to lessen its status as compared to Sunday or “The Lord’s Day” (as it was eventually termed – but not until late in the second century when the term “The Lord’s Day” was first used in reference to Sunday by Clement of Alexandria), to cope with Roman laws against Sabbathkeeping – to include Justin Martyr (100-165 AD), Irenaeus (130-202 AD), Pothinus (87-177 AD), Tertullian (160-220 AD), Clement (150-215 AD), and Origen (185-254 AD).

Justin Martyr (100-165 AD):

Of course, many started to allegorize the meaning and purpose of the Sabbath – according to the teachings of the Gnostics which heavily influenced those in Rome and Alexandria beginning within the 2nd Century. For example, Justin Martyr wrote:

Of course, many started to allegorize the meaning and purpose of the Sabbath – according to the teachings of the Gnostics which heavily influenced those in Rome and Alexandria beginning within the 2nd Century. For example, Justin Martyr wrote:

“The Lawgiver is present, yet you do not see Him; to the poor the Gospel is preached, the blind see, yet you do not understand. You have now need of a second circumcision, though you glory greatly in the flesh. The new law requires you to keep perpetual sabbath, and you, because you are idle for one day, suppose you are pious, not discerning why this has been commanded you: and if you eat unleavened bread, you say the will of God has been fulfilled. The Lord our God does not take pleasure in such observances: if any one has impure hands, let him wash and be pure; if there is any perjured person or a thief among you, let him cease to be so; if any adulterer, let him repent; then he has kept the sweet and true sabbaths of God. “

Dialogue with Trypho the Jew Chapter XII.

For we too would observe the fleshly circumcision, and the Sabbaths, and in short all the feasts, if we did not know for what reason they were enjoined you,—namely, on account of your transgressions and the hardness of your hearts. For if we patiently endure all things contrived against us by wicked men and demons, so that even amid cruelties unutterable, death and torments, we pray for mercy to those who inflict such things upon us, and do not wish to give the least retort to any one, even as the new Lawgiver commanded us: how is it, Trypho, that we would not observe those rites which do not harm us, —I speak of fleshly circumcision, and Sabbaths, and feasts?

Dialogue with Trypho the Jew Chapter XVIII.

“Wherefore, Trypho, I will proclaim to you, and to those who wish to become proselytes, the divine message which I heard from that man. Do you see that the elements are not idle, and keep no Sabbaths? Remain as you were born. For if there was no need of circumcision before Abraham, or of the observance of Sabbaths, of feasts and sacrifices, before Moses; no more need is there of them now, after that, according to the will of God, Jesus Christ the Son of God has been born without sin, of a virgin sprung from the stock of Abraham. For when Abraham himself was in uncircumcision, he was justified and blessed by reason of the faith which he reposed in God, as the Scripture tells. Moreover, the Scriptures and the facts themselves compel us to admit that He received circumcision for a sign, and not for righteousness…

As, then, circumcision began with Abraham, and the Sabbath and sacrifices and offerings and feasts with Moses, and it has been proved they were enjoined on account of the hardness of your people’s heart, so it was necessary, in accordance with the Father’s will, that they should have an end in Him who was born of a virgin, of the family of Abraham and tribe of Judah, and of David; in Christ the Son of God, who was proclaimed as about to come to all the world, to be the everlasting law and the everlasting covenant, even as the forementioned prophecies show.”

The Second Apology of Justin for the Christians, Addressed to the Roman Senate. Chapter XXIII and XLIII

As an aside, if Sunday was known as the “Lord’s day” during the last of the first and the early part of the second century, how can we explain the fact that the two strongest advocates of Sunday observance in the second century, Barnabas and Justin Martyr (in fact, the only ones who actually denounced Sabbath observance and urged the observance of Sunday in that period – most of the rest of the church leaders and members during this time clearly continued to observe the Sabbath day as a day of worship) never referred to Sunday as “the Lord’s day”? Although they were trying to find a reason for observing Sunday, yet they always referred to it simply as the first day, or the eighth day; and in one instance Justin used the heathen expression, “he tou heliou hemera,” the day of the sun, in referring to it. If Sunday was then known as “The Lord’s Day,” and these men were urging the observance of it as a replacement for the Sabbath, why did they not use that title, and cite the apostle John as their example? All this seems to indicate that these men and their associates knew nothing about Sunday as “The Lord’s Day.”

In any case, it is quite evident that the idea of being able to keep the Sabbath without actually being “idle,” as were the Jews, was rather widespread among the early second century Christians – despite those like Justin Martyr who wanted to give up the concept of Sabbath observance altogether. Christians during this time faced the constant possibility that, because of some adverse event, the pagans would rise up against them and accuse them, yet again, of causing the gods to become angry. Thus, Christian leaders did what they could to demonstrate by their lives that they were upright, noble citizens – not at all like the unruly Jews.

All this taken into account sufficiently distinguished the Christians from the Jews regarding Sabbath observance in the eyes of the Romans who were, during Hadrian’s time, primarily targeting the Jews themselves. Also, Hadrian’s laws were not evenly enforced throughout the Roman Empire.

However, there is no doubt that the various attitudes of Christians relating to the Sabbath laws of Rome during the second and third centuries paved the way for the more drastic changes that took place in the fourth century, especially during the reign of Emperor Constantine.

Never the less, Sabbath-keeping, the original position of the Church, had already spread west into Europe from Palestine. It spread East into India (Mingana, Early Spread of Christianity, Vol. 10, p. 460) and then into China.

Irenaeus (130-202 AD):

Irenaeus also acknowledged that Christ did not do away with the Decalogue or the law of the Sabbath within the Decalogue.

Irenaeus also acknowledged that Christ did not do away with the Decalogue or the law of the Sabbath within the Decalogue.

“Perfect righteousness was conferred neither by any other legal ceremonies. The decalogue however was not cancelled by Christ, but is always in force: men were never released from its commandments.” (ANF, Bk. IV, Ch. XVI, p. 480)

He emphasized, in contrast to the common Jewish position, however, that Jesus said, “It is lawful to do good on the Sabbath” (Matt. 12:12, NKJV). It followed, then, that humanity need not be idle on the Sabbath:

“And therefore the Lord reproved those who unjustly blamed Him for having healed upon the Sabbath-days. For He did not make void, but fulfilled the law. . . . And again, the law did not forbid those who were hungry on the Sabbath-days to take food lying ready at hand: it did, however, forbid them to reap and to gather into barns.”

Beyond this, however, Irrenaeus argued that Sabbath observance, on the 7th-day, was not really necessary – since, according to him, the Patriarchs before Moses did not observe the Sabbath.

“Abraham himself, without circumcision and without observance of Sabbaths, believed God, and it was imputed unto him for righteousness; and he was called the friend of God. James 2:23 Then, again, Lot, without circumcision, was brought out from Sodom, receiving salvation from God. So also did Noah, pleasing God, although he was uncircumcised, receive the dimensions [of the ark], of the world of the second race [of men]. Enoch, too, pleasing God, without circumcision, discharged the office of God’s legate to the angels although he was a man, and was translated, and is preserved until now as a witness of the just judgment of God, because the angels when they had transgressed fell to the earth for judgment, but the man who pleased [God] was translated for salvation. Moreover, all the rest of the multitude of those righteous men who lived before Abraham, and of those patriarchs who preceded Moses, were justified independently of the things above mentioned, and without the law of Moses. As also Moses himself says to the people in Deuteronomy: The Lord your God formed a covenant in Horeb. The Lord formed not this covenant with your fathers, but for you.” Deuteronomy 5:2

Iranaeus, Against Heresies, (Book IV, Chapter 16 – Link)

Tertullian (160-220 AD):

Tertullian pointed out:

Tertullian pointed out:

“It is lawful to do good on the Sabbath” (Mark 3:4) and went on to explain, “For when it says of the Sabbath-day, ‘In it thou shalt not do any work of thine,’ by the word thine it restricts the prohibition to human work—which everyone performs in his own employment or business—and not to divine work.”

However, Tertullian went on to attack Sabbath observance in more direct terms:

“[L]et him who contends that the Sabbath is still to be observed as a balm of salvation, and circumcision on the eighth day . . . teach us that, for the time past, righteous men kept the Sabbath or practiced circumcision, and were thus rendered ‘friends of God.’ For if circumcision purges a man, since God made Adam uncircumcised, why did he not circumcise him, even after his sinning, if circumcision purges? . . . Therefore, since God originated Adam uncircumcised and unobservant of the Sabbath, consequently his offspring also, Abel, offering him sacrifices, uncircumcised and unobservant of the Sabbath, was by him [God] commended [Gen. 4:1–7, Heb. 11:4]. . . . Noah also, uncircumcised—yes, and unobservant of the Sabbath—God freed from the deluge. For Enoch too, most righteous man, uncircumcised and unobservant of the Sabbath, he translated from this world, who did not first taste death in order that, being a candidate for eternal life, he might show us that we also may, without the burden of the law of Moses, please God”

An Answer to the Jews Chapter II.

As far as Sunday observance, it was, according to Tertullian, all based on tradition – not on scripture:

We count fasting or kneeling in worship on the Lord’s day to be unlawful. We rejoice in the same privilege also from Easter to Whitsunday. We feel pained should any wine or bread, even though our own, be cast upon the ground. At every forward step and movement, at every going in and out, when we put on our clothes and shoes, when we bathe, when sit at table, when we light the lamps, on couch, on seat, in all the ordinary actions of daily life, we trace upon the forehead the sign [of the cross].

If, for these and other such rules, you insist upon having positive Scripture injunction, you will find none. Tradition will be held forth to you as the originator of them, custom, as their strengthener, and faith, as their observer. That reason will support tradition, and custom, and faith, you will either yourself perceive, or learn from some one who has.

Tertullian, De Corona, Sects. 3 and 4.

Then again, at times, Tertullian appears to actually give preference to the Sabbath – even over the observance of “the eighth day”:

For my own part, I prefer viewing this measure of time in reference to God, as if implying that the ten months rather initiated man into the ten commandments; so that the numerical estimate of the time needed to consummate our natural birth should correspond to the numerical classification of the rules of our regenerate life. But inasmuch as birth is also completed with the seventh month, I more readily recognize in this number than in the eighth the honor of a numerical agreement with the Sabbatical period; so that the month in which God’s image is sometimes produced in a human birth, shall in its number tally with the day on which God’s creation was completed and hallowed.

Tertullian, De Anima, chap 37.

In presenting such an argument Tertullian appears to show his faith in the Ten Commandments as the rule that should govern the Christian’s life – and even gives preference to the seventh day as the Sabbath, the origin of which is from God’s act of hallowing the seventh day at creation.

Occasionally, Tertullian also appears to put on equal footing the Sabbath and the Lord’s Day (or Sunday). In this treatise “On Fasting,” chapter 14., he terms “the Sabbath – a day never to be kept as a fast except at the Passover season, according to a reason elsewhere given.” And, in chapter 15., Tertullian exempts from the two weeks in which meat was not eaten “the Sabbaths” and “the Lord’s days.”

He next declares that Isaiah’s prediction respecting the Sabbath in the new earth (Isaiah 66:22, 23), was “fulfilled in the time of Christ, when all flesh – that is, every nation came to adore in Jerusalem God the Father… Thus, therefore, before this temporal Sabbath [the seventh day], there was withal an eternal Sabbath foreshown and foretold.”

In chapter 6, Tertullian repeats his theory of the “Sabbath temporal” [the seventh day], and the “Sabbath eternal” or the “Spiritual Sabbath,” which is “to observe a Sabbath from all ‘servile works’ always, and not only every seventh day, but through all time.” He says that the ancient law has ceased, and that “the new law” and the Spiritual Sabbath has come whereby every day is the Sabbath.

Yet, in a seeming backpeddle, Tertullian appears to claim that Jesus never actually broke the Sabbath nor did Jesus do away with the Sabbath:

In order that he might, whilst allowing that amount of work which he was about to perform for a soul, remind them what works the law of the Sabbath forbade – even human works; and what it enjoined – even divine works, which might be done for the benefit of any soul, he was called ‘Lord of the Sabbath’ because he maintained the Sabbath as his own institution. Now, even if he had annulled the Sabbath, he would have had the right to do so, as being its Lord, [and] still more as he who instituted it. But he did not utterly destroy it, although its Lord, in order that it might henceforth be plain that the Sabbath was not broken by the Creator, even at the time when the ark was carried around Jericho. For that was really God’s work, which he commanded himself, and which he had ordered for the sake of the lives of his servants when exposed to the perils of war.

Tertullian, Book iv. chap 12.

In this paragraph, Tertullian explains the law of God in the clearest manner. He shows beyond all dispute that neither Joshua nor Christ ever violated it. He also declares that Christ did not abolish the Sabbath. He further explains this seemly contradictory position as follows:

Now, although he has in a certain place expressed an aversion of Sabbaths, by calling them ‘your Sabbaths,’ reckoning them as men’s Sabbaths, not his own, because they were celebrated without the fear of God by a people full of iniquities, and loving God ‘with the lip, not the heart,’ he has yet put his own Sabbaths (those, that is, which were kept according to this prescription) in a different position; for by the same prophet, in a later passage, he declares them to be ‘true, delightful, and inviolable.’ [Isaiah 58:13; 56:2.] Thus Christ did not at all rescind the Sabbath: he kept the law thereof, and both in the former case did a work which was beneficial to the life of his disciples (for he indulged them with the relief of food when they were hungry), and in the present instance cured the withered hand; in each case intimating by facts, ‘I came not to destroy the law, but to fulfill it,’ although Marcion has gagged his mouth by this word.

Tertullian, Book iv. chap 12.

Here Tertullian shows that God did not hate his own Sabbath, but only the hypocrisy of those who professed to keep it. He also expressly declares that the Saviour “did not at all rescind the Sabbath.” He continues as follows:

For even in the case before us he fulfilled the law while interpreting its condition; [moreover] he exhibits in a clear light the different kinds of work, while doing what the law except from the sacredness of the Sabbath, [and] while imparting to the Sabbath day itself which from the beginning had been consecrated by the benediction of the Father, an additional sanctity by his own beneficent action. For he furnished to this day divine safeguards – a course which his adversary would have pursued for some other days, to avoid honoring the Creator’s Sabbath, and restoring to the Sabbath the works which were proper for it. Since, in like manner, the prophet Elisha on this day restored to life the dead son of the Shunammite woman, you see, O Pharisee, and you too, O Marcion, how that it was [proper employment] for the Creator’s Sabbaths of old to do good, to save life, not to destroy it; how that Christ introduced nothing new, which was not after the example, the gentleness, the mercy, and the prediction also of the Creator. For in this very example he fulfills the prophetic announcement of a specific healing: ‘The weak hands are strengthened’, as were also ‘the feeble knees’ in the sick of the palsy.”

Tertullian against Marcion, b. iv. chap 12.

Although Tertullian is mistaken here in his reference to the Shunammite woman (It was not the Sabbath day on which she went to the prophet: 2 Kings 4:23), he affirms many important truths here.

What we have then in the person of Tertullian is someone who very conflicting thoughts and statements. He often contradicts himself in the most extraordinary manner concerning the Sabbath and the law of God. He asserts that the Sabbath was abolished by Christ, and elsewhere emphatically declares that he did not abolish it. He says that Joshua violated the Sabbath, and then expressly declares that he did not violate it. He says that Christ broke the Sabbath and then shows that he never did this. He represents the eighth day as more honorable than the seventh, and elsewhere states just the reverse. He asserts that the law is abolished, and in other places affirms its perpetual obligation. He speaks of the Lord’s day as the eighth day, (the second of the early writers who makes an application of this term to Sunday, with Clement of Alexandria, A. D. 194, being the first). Also, like Clement, Tertullian uses the term “the eighth day” and teaches a “perpetual Lord’s day” – or, like Justin Martyr, a “perpetual Sabbath” in the observance of every day. He also promotes the bringing of “offerings for the dead” on the Lord’s day – and the perpetual use of the sign of the cross. However, Tertullian expressly affirms that these things rest, not upon the authority of the Scriptures, but wholly upon that of tradition and custom. And, although he speaks of the Sabbath as abrogated by Christ, he expressly contradicts this assertion by writing that Christ “did not at all rescind the Sabbath.” Beyond this, Tertullian argues that Jesus imparted an additional sanctity to the Sabbath day – which “from the beginning had been consecrated by the benediction of the Father.”

This strange mingling of truth and error plainly indicates the age in which Tertullian lived. He was not so far removed from the time of the apostles but that many clear rays of divine truth shone upon him. Yet, he was far enough advanced in the age of compromise with pagan concepts and secular civil laws against the Sabbath that he stood on the line between expiring day and advancing night.

See also the commentary of J. N. Andrews on Tertullian: Link

Clement (150-215 AD):

Clement of Alexandria wrote in a similar Gnostic manner regarding Sabbath observance for the Christian:

Clement of Alexandria wrote in a similar Gnostic manner regarding Sabbath observance for the Christian:

“For the teacher of him who speaks and of him who hears is one—who waters both the mind and the word. Thus the Lord did not hinder from doing good while keeping the Sabbath; but allowed us to communicate of those divine mysteries, and of that holy light to those who are able to receive them.”

Of course, so far this seems fairly straightforward. However, Clement goes on to argue more clearly along Gnostic lines as follows:

“The eight day appears rightly to be named the seventh, and to be the true Sabbath, but the seventh to be a working day.”

Rev. A.A. Phelps, in “An Argument for the Perpetuity of the Sabbath,” p. 159

Here Clement argues that Sunday is really the seventh day and that the seventh day (Sabbath) is really the sixth day – and goes on to explain that Sunday is a work day of ordinary labor while Saturday remains a day of rest. Clement proceeds at length to show the sacredness and importance of the number six – which for him is the Saturday the Sabbath. (Link)

It is also a striking coincidence that the first mention of Sunday as a mystic “eighth day” should be found in the Gnostic pseudo-Barnabas (Link), and that the first mention of the term “Lord’s Day” as a mystic day typifying the renewed life should be made by the Gnostic philosopher Clement of Alexandria – the very one who first endorsed this pseudo-epistle as valid scripture. He was also the first to forward the solar day of the Pagans as the mystical “eighth day” of the Lord (represented by Sunday and the resurrection with Christ into a new world and a new eternal age of light).

“And they purify themselves seven days, the period in which creation was consummated. For on the seventh day the rest is celebrated; and on the eighth, he brings a propitiation, as it is written in Ezekiel, according to which propitiation the promise is to be received.”

Clement, Book iv. chap 25.

Again, the following quote is the first instance in the writings of the Christian fathers in which the term “the Lord’s day” is expressly applied to Sunday. However, Clement does not say that he inherited this concept from Saint John or any other apostle of Christ. Rather, he finds authority for this in the writings of the Greek philosopher Plato, of all people, whom Clement thinks spoke of this concept prophetically!

And the Lord’s day Plato prophetically speaks of in the tenth book of the Republic, in these words: ‘

And when seven days have passed to each of them in the meadow, on the eighth day they are to set out and arrive in four days,’

By the meadow is to be understood the fixed sphere, as being a mild and genial spot, and the locality of the pious; and by the seven days each motion of the seven planets, and the whole practical art which speeds to the end of the rest. But after the wandering orbs the journey leads to Heaven, that is, to the eighth motion and day. And he says that souls are gone on the fourth day, pointing out the passage through the four elements.”

Clement, Book v. chap 14.

By the “eighth day” to which Clement here applies the name of the “Lord’s Day” is no doubt intended the first day of the week. However, having presented arguments in favor of the eighth day, Clement, in the very next sentence, tries to establish, from the Greek philosophers no less, the sacredness of that seventh day. This shows that whatever regard he might have for the eighth day, he certainly thought of the seventh day as sacred as well…

But the seventh day is recognized as sacred, not by the Hebrews only, but also by the Greeks; according to which the whole world of all animals and plants revolves.

Hesiod says of it:-

‘The first, and fourth, and seventh days were held sacred.’

And again: ‘And on the seventh the sun’s resplendent orb.’And Homer: ‘And on the seventh then came the sacred day.’

And: ‘The seventh was sacred.’

And again: ‘It was the seventh day, and all things were accomplished.’

And again: ‘And on the seventh morn we leave the stream of Acheron.’Callimachus the poet also writes: ‘It was the seventh morn, and they had all things done.’

And again: ‘Among good days is the seventh day, and the seventh race.’ And: ‘The seventh is among the prime, and the seventh is perfect.’

And: ‘Now all the seven were made in starry heaven, In circles shining as the years appear.’The Elegies of Solon, too, intensely deify the seventh day.

Clement, Book v. chap 14.

See also the review of J.N. Andrews: Link

Origen (185-254 AD):

Likewise, Origen (a disciple of Clement of Alexandria) argued that Christian Sabbath observance should be different from Jewish Sabbath observance:

Likewise, Origen (a disciple of Clement of Alexandria) argued that Christian Sabbath observance should be different from Jewish Sabbath observance:

“It is fitting for whoever is righteous among the saints to keep also the festival of the Sabbath. Which is, indeed, the festival of the Sabbath, except that concerning which the Apostle said, ‘There remaineth therefore a sabbatismus, that is, a keeping of the Sabbath, to the people of God [Hebrews 4:9]’. Forsaking therefore the Judaic observance of the Sabbath, let us see what sort of observance of the Sabbath is expected of the Christian. On the day of the Sabbath nothing of worldly acts ought to be performed…”

Homily on Numbers 23, para. 4, in Migne, Patrologia Græca, Vol. 12, cols. 749, 750

Beyond this, however, Origen argued that the Christian should live as if every day were holy to God, and clearly indicated that Sunday was considered a day of worship by Christians in his day – along with the Sabbath:

“If it be objected to us on this subject that we ourselves are accustomed to observe certain days, as for example the Lord’s day, the Preparation, the Passover, or Pentecost, I have to answer, that to the perfect Christian, who is ever in his thoughts, words, and deeds serving his natural Lord, God the Word, all his days are the Lord’s, and he is always keeping the Lord’s day.”

Origen Against Celsus. Book 8 Chapter XXII.

This wasn’t the only issue with Origen’s efforts to harmonize Christianity with Gnostic philosophy.

“In his attempt to reconcile the gospel and his philosophy he miserably compromises some of the most important truths of Scripture… [Origen] maintained the pre-existence of human souls, he held that the stars are animated beings; he taught that all men shall ultimately attain happiness; and he believed that the devils themselves shall eventually be saved.”

Killen, “Ancient Church,” second period, sec. 2, chap. I.

It is no wonder then that Origen wrote in such mystical terms regarding the Sabbath and the “Lord’s Day” – as well as many other Christian Doctrines.

“There are countless multitudes of believers who. . .are most firmly persuaded that neither ought circumcision to be understood literally, nor the rest of the Sabbth, nor the pouring out of the blood of an animal, nor that answers were given by God to Moses on these points.”

Origen, De Principiis, b. ii. chap 7 (Link)

Origen continually asserts that the spiritual interpretation of the Scriptures, whereby their literal meaning is set aside, is something divinely inspired. But, when this notion is accepted as the truth who can tell what is actually intended by the author? Truth starts to become what anyone wants it to be – kind of like interpreting modern art. And, this is how Origen interpreted the concept of the Sabbath in Scripture as well. He seem to recognize the origin of the Sabbath at the beginning of creation, but still gives it a hidden mystical meaning:

“For he [Celsus] knows nothing of the day of the Sabbath and rest of God, which follows the completion of the world’s creation, and which lasts during the duration of the world, and in which all those will keep festival with God who have done all their works in their six days, and who, because they have omitted none of their duties, will ascend to the contemplation [of celestial things], and to the assembly of righteous and blessed beings.”

Origen, Book vi. chap. 1xi. TFTC 86.4

Here we get an insight into Origen’s mystical Sabbath. It began at creation and will continue while the world endures. To those who follow the letter it is indeed only a weekly rest, but to those who know the truth, it is a perpetual Sabbath enjoyed by God during all the days of time and entered by believers either at conversion or at death.

This is true with regard to Sunday-observance as well – or the “Lord’s Day”. Origen divided his brethren into two classes. In one class are the imperfect Christians who content themselves with the literal day while in the other class are the “perfect Christians” whose Lord’s day embraces all the days of life.

Undoubtedly, Origen reckoned himself one of the perfect Christians since his own observance of the Lord’s day did not consist in the elevation of one day above another – for he counted them all alike as constituting one perpetual Lord’s day. This is the same doctrine promoted by Clement of Alexandria, who was Origen’s teacher in his early life. The keeping of the Lord’s day with Origen (as with Clement) embraced all the days of his life and consisted, according to Origen, in serving God in thought, word, and deed, continually. Or, as expressed by Clement, one “keeps the Lord’s [Day], when he abandons an evil disposition and assumes that of the Gnostic.”

Augustine of Hippo (354-430 AD):

Augustine of Hippo, regarding why the Christian no longer needed to observe the Sabbath wrote:

So, when you ask why a Christian does not keep the Sabbath, if Christ came not to destroy the law, but to fulfill it, my reply is, that a Christian does not keep the Sabbath precisely because what was prefigured in the Sabbath is fulfilled in Christ. For we have our Sabbath in Him who said, “Come unto me, all ye that labor and are heavy laden, and I will give you rest. Take my yoke upon you, and learn of me; for I am meek and lowly in heart, and ye shall find rest unto your souls.”

Augustine of Hippo: Reply to Faustus the Manichæan. Book XIX.-9

Sabbath vs. Sunday:

Emperor Constantine (274-337 AD):

The increase in references about the Sabbath in early Christian church literature, both for and against, indicate that some sort of struggle was beginning to manifest itself on a rather widespread basis. The controversy wasn’t so much about Sunday observance, for that had long been established in most Christian communities throughout the Christian world. The problem was over continued Sabbath observance, which was also just as widespread throughout Christendom for the first several centuries. Some thought that a Sabbath fast should be imposed while others strongly rejected burdening the seventh-day Sabbath with fasting. Some wanted everyone to work on the Sabbath “doing good” and others wanted to maintain the Sabbath as a day of complete rest and idleness – similar to the way the Jews observed the Sabbath. And, of course, there were those who wanted to do away completely with Sabbath observance in order to get rid of all traces of Judaism.

The increase in references about the Sabbath in early Christian church literature, both for and against, indicate that some sort of struggle was beginning to manifest itself on a rather widespread basis. The controversy wasn’t so much about Sunday observance, for that had long been established in most Christian communities throughout the Christian world. The problem was over continued Sabbath observance, which was also just as widespread throughout Christendom for the first several centuries. Some thought that a Sabbath fast should be imposed while others strongly rejected burdening the seventh-day Sabbath with fasting. Some wanted everyone to work on the Sabbath “doing good” and others wanted to maintain the Sabbath as a day of complete rest and idleness – similar to the way the Jews observed the Sabbath. And, of course, there were those who wanted to do away completely with Sabbath observance in order to get rid of all traces of Judaism.

However, the controversy over Sabbath observance increased significantly within the fourth and fifth centuries and expanded well beyond Rome and Alexandria. What could have triggered this conflict on such a wide scale in the fourth and fifth centuries? Undoubtedly, one of the most important factors is to be found in the activities of Emperor Constantine the Great in the early fourth century – and subsequently by other “Christian Emperors.”

Not only did Constantine give Christianity a new status within the Roman Empire (from being persecuted to being honored), but he also gave Sunday a “new look.” By his civil legislation, he made Sunday an official rest day of the state. His famous Sunday law of March 7, 321, reads:

“On the venerable Day of the Sun let the magistrates and people residing in cities rest, and let all workshops be closed. In the country, however, persons engaged in agriculture may freely and lawfully continue their pursuits; because it often happens that another day is not so suitable for grain–sowing or for vine–planting; lest by neglecting the proper moment for such operations the bounty of heaven should be lost.”

Codex Justinianus, iii., Tit. 12.3, trans. in Philip Schaff, History of the Christian Church, 5th ed. (New York, 1902), Vol. 3, p. 380, note 1.

This was the first in a series of steps taken by Constantine, and by later Christian Emperors, in regulating Sunday observance according to national civil laws. It is obvious that this first Sunday law was not particularly Christian in orientation (note the pagan designation “venerable Day of the Sun”). However, Constantine, on political and social grounds, was ever endeavoring to merge together heathen and Christian elements of his constituency by focusing on a common practice.

“Constantine’s decrees marked the beginning of a long though intermittent series of imperil decrees in support of Sunday rest.”

A History of the Councils of the Church, volume 2, page 316.

“What began as a pagan ordinance, ended as a Christian regulation; and a long series of imperial decrees, during the fourth, fifth, and sixth centuries, enjoined with increasing stringency abstinence from labor on Sunday.”

Hutton Webster, Rest Days, 1916, pp. 122-123, 270. [Webster (1875-1955) was an anthropologist and historian at the University of Nebraska].

In 386 AD, Theodosius I and Gratian Valentinian extended Sunday restrictions so that litigation should entirely cease on that day and there would be no public or private payment of debt. Laws forbidding circus, theater, and horse racing also followed and were reiterated as felt necessary.

Theodosian Code, 11.7.13, trans. by Clyde Pharr (Princeton, N.J., 1952), p. 300.

Constantine enacted several Sunday laws during his reign (306-337 A.D.) followed by at least fifteen additional Sunday decrees within the next few centuries after his death – including Governmental decrees in the years 365, 386, 389, 458, 460, 554, 589, 681, 768, 789, and onward and church council decrees in 343, 538, 578, 581, 690 and onward. These laws restricted what could be done on Sunday and forbade Sabbath keeping. Each law became more and more strict, each penalty more and more severe. This, in itself, is strong evidence of the continued desire by many Christians, throughout the Christian world, to continue to keep the 4th Commandment of the Decalogue of God. In fact, in the centuries following Emperor Constantine, there was a significant revival in Sabbath observance within the majority of Christian Churches throughout Christendom.

Gregory of Nyssa (335-394):

Still, the concept of the Sabbath as a holy day held on in the Christian world.

Gregory of Nyssa, also known as Gregory Nyssen, was bishop of Nyssa from 372 to 376 and from 378 until his death. He is venerated as a saint in Roman Catholicism, Eastern Orthodoxy, Oriental Orthodoxy, Lutheranism, and Anglicanism. Yet, even during this time, following the decrees of Constantine, Gregory wrote about the equality of the Sabbath day with the “Lord’s Day”, or Sunday worship:

With what eyes can you behold the Lord’s day, when you despise the Sabbath? Do you not perceive that they are sisters, and that in slighting the one, you affront the other?

Expostulation of Gregory of Nyssa, 372 AD, Dialogues on the Lord’s day, p. 188; Hessey’s Bampton Lectures, pp. 72, 304, 305.

Spain – Council of Elvira (A.D.305):

Canon 26 of the Council of Elvira reveals that the Church of Spain at that time kept Saturday, the seventh day.

“As to fasting every Sabbath: Resolved, that the error be corrected of fasting every Sabbath.”

This resolution of the council is in direct opposition to the policy the church at Rome had inaugurated, that of commanding Sabbath as a fast day in order to humiliate it and make it repugnant to the people.

Persia (335-375 AD):