Limited

Evolutionary Potential

Sean

D. Pitman M.D.

©

November 2006

The

Claim

Michael

Behe, professor of biochemistry at Lehigh University, boldly claims that,

"Molecular evolution is not based on scientific authority.

There is no publication in the scientific literature in prestigious

journals, specialty journals, or books that describe how molecular evolution of

any real, complex, biochemical system either did occur or even might have

occurred. There are assertions that

such evolution occurred, but absolutely none are supported by pertinent

experiments or calculations." 1

Michael

Behe, professor of biochemistry at Lehigh University, boldly claims that,

"Molecular evolution is not based on scientific authority.

There is no publication in the scientific literature in prestigious

journals, specialty journals, or books that describe how molecular evolution of

any real, complex, biochemical system either did occur or even might have

occurred. There are assertions that

such evolution occurred, but absolutely none are supported by pertinent

experiments or calculations." 1

The

Controversy

Since

the publishing of Behe's book, Darwin's

Black Box in 1996, a fair bit of controversy has arisen over such

statements. Surprisingly, many

evolutionary scientists seem to grudgingly agree with Behe, at least in some

limited way. For example, microbiologist James Shapiro of

the University of Chicago declared in National Review that, "There

are no detailed Darwinian accounts for the evolution of any fundamental

biochemical or cellular system, only a variety of wishful speculations"

(Shapiro 1996). In Nature, University of Chicago evolutionary

biologist, Jerry Coyne, noted that, "There is no doubt that the pathways

described by Behe are dauntingly complex, and their evolution will be hard to

unravel. . . . [W]e may forever be unable to envisage the first

proto-pathways" (Coyne 1996). In Trends in Ecology and Evolution

Tom Cavalier-Smith, an evolutionary biologist at the University of British

Columbia, wrote, "For none of the cases mentioned by Behe is there yet a

comprehensive and detailed explanation of the probable steps in the evolution of

the observed complexity. The problems have indeed been sorely neglected--though

Behe repeatedly exaggerates this neglect with such hyperboles as 'an eerie and

complete silence'" (Cavalier-Smith 1997). Evolutionary biologist,

Andrew Pomiankowski, agreed. In New Scientist, he challenged anyone to,

"Pick up any biochemistry textbook, and you will find perhaps two or three

references to evolution. Turn to one of these and you will be lucky to find

anything better than 'evolution selects the fittest molecules for their

biological function'" (Pomiankowski 1996). In American Scientist,

Yale molecular biologist, Robert Dorit, suggested that, "In a narrow sense,

Behe is correct when he argues that we do not yet fully understand the evolution

of the flagellar motor or the blood clotting cascade" (Dorit 1997). 7

Observing

the Evolution of a Complex System

Obviously

though, there are many more scientists who passionately disagree with Behe's

position. These scientists argue quite strongly that the mechanism is

known in detail and that it is observed in action all the time producing

"irreducibly complex" systems with complex specified information.

Perhaps one of Behe's

better opponents is Kenneth Miller (biologist, Brown University).

In his 1999 book, Finding

Darwin's God, one of Miller's challenges of Behe's position includes a

1982 research study by professor Barry Hall, an biologist from the

University of Rochester.

What

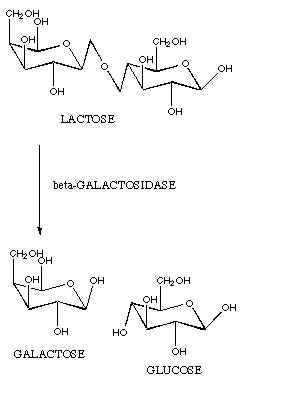

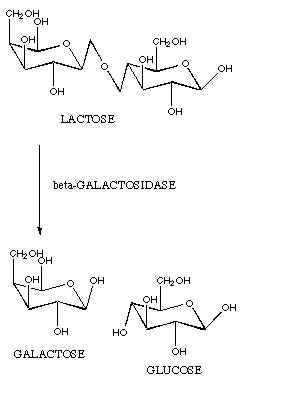

Hall did was indeed very interesting. He

deleted a gene (lacZ) in a type of bacteria (E.

coli) that makes a lactase enzyme (galactosidase).

This lactase enzyme converts a sugar called lactose into the sugars

glucose and galactose. E.

coli then process glucose and galactose further to extract energy.

One might think that when Hall deleted the gene that codes for the

lactase enzyme that these bacteria would never be able to use lactose for energy

again. However, when Hall exposed

the mutant bacteria to lactose enriched growth media, that they quickly

modified a different gene, which Hall named the "evolved Beta-galactosidase

gene" (ebg), to produce a pretty good lactase enzyme.

This is interesting because the original gene product did not have the lactase

function. Only after a key random mutation was this genetic sequence able

to produce a protein with the lactase function.2, 3

Behe

counters by arguing that as far as the active sites of the lac and

ebg Beta-galactosidase enzymes are concerned, that they are

essentially the same with both being a part of a family of highly conserved Beta-galactosidases

- identical at 13 of 15 active-site amino acid residues. The two mutations

in the ebg Beta-galactosidase, that increase its ability

to hydrolyze lactose, change the two non-identical residues back to those of the

other Beta-galactosidases. So, before the evolution of the lactase

ability of the ebg gene, its active site was already a near duplicate of

other Beta-galactosidases.8

Even so, this really was quite an amazing experiment in that a novel

enzymatic function, which was not present in the entire gene pool prior

random mutation and natural selection, did in fact evolve in real time.

According to Miller and Hall, and many others quoting the same or similar

experiments, such experiments give demonstrable proof of the proposed

evolutionary mechanism in action. Obviously

then, Behe does not know what he is talking about . . . or does he? Consider

that fairly often things are not quite as they would appear at first glance.

Even so, this really was quite an amazing experiment in that a novel

enzymatic function, which was not present in the entire gene pool prior

random mutation and natural selection, did in fact evolve in real time.

According to Miller and Hall, and many others quoting the same or similar

experiments, such experiments give demonstrable proof of the proposed

evolutionary mechanism in action. Obviously

then, Behe does not know what he is talking about . . . or does he? Consider

that fairly often things are not quite as they would appear at first glance.

At

First Glance

At

first glance, Hall's experiment does indeed seem to be a "real time"

example of improvement through mutation and natural selection.

Obviously then, this is evolution in action. Certainly it is, but

it might be a bit different from what one might expect.

It

is not a difficult thing to evolve a particular function if that function is

only one point mutation (one step) away from realization. The odds that one

particular point mutation will happen rapidly in an average sized bacterial

colony are extremely good. A random step/mutation across such a small gap isn't

a problem at all. The real question is, what are the odds that such a

potentially beneficial protein-based structure will actually exist in the

potential of sequence space just one step away from what is currently present

within a given genome? It is this question that those like Hall and Miller

and other evolutionary scientists do not address.

However,

if a small crack in the evolutionary sidewalk can be crossed, why can't these

cracks be added up over time, one new little function at a time, until we end up

with the awesome complexity and variations of life forms that we see today? After

all, the

theory of evolution is based on a fairly simple idea that random mutations

create diversity while natural selection acts as a guide to select those changes

that best aid the survival of that gene pool. Thus, evolution, when it

happens, is not truly a random process - although random events are involved in

the process. Natural selection guides the changes over time, adding them

together, one by one, until the vast diversity of life forms that we see today

is the result. Certainly then, it should at least be technically possible

to add even the smallest changes together over time to produce all the variety

in life forms and functionally complex biofunctions that we see in the world today. Certainly this sounds like

quite a reasonable possibility - at first glance.

A

Closer Look

Most

descriptions of Hall's experiments end with E. coli evolving the lactase function back again. This is

very interesting because Hall's actual experiments did not end there.

After his initial success, Hall wondered if any other genes would be able to

evolve the lactase function. So, he deleted the ebg gene as well as

the lacZ genes to test this hypothesis. And, something most

interesting happened - nothing. No new gene or portion of DNA evolved the

lactase function despite tens of thousands of generations of time, a huge

population size, high selection pressure, and a high mutation rate. Now

that is just fascinating . . .

In

order to understand what happened, lets consider Hall's experiment in just

a little more detail. Behe summarizes Hall's

methods pretty well in the following description:

Without

Beta-galactosidase, Hall's cells could not grow when cultured on a medium

containing only lactose as a carbon source. However, when grown on a plate

that also included alternative, useable nutrients, bacterial colonies could

be established. When the other nutrients were exhausted the colonies stopped

growing. However, Hall noticed that after several days to several weeks,

hyphae grew on some of the colonies. Upon isolating cells from the hyphae,

Hall saw that they frequently had two mutations, one of which was in a gene

for a protein he called "evolved Beta-galactosidase," ("ebg")

which allowed it to metabolize lactose efficiently. (Despite considerable

efforts by Hall to determine it, the natural function of ebg

remains unknown) (Hall 1999). The ebg

gene is located in another operon, distant from the lac

operon, and is under the control of its own repressor protein. The second

mutation Hall found was always in the gene for the ebg

repressor protein, which caused the repressor to bind lactose with

sufficient strength to de-repress the ebg

operon.

The

fact that there were two separate mutations in different genes—neither of

which by itself allowed cell growth (Hall 1982a) - startled Hall, who knew

that the odds against the mutations appearing randomly and independently

were prohibitive (Hall 1982b). Hall's results and similar results from

other laboratories led to research in the area dubbed "adaptive

mutations." (Cairns 1998; Foster 1999; Hall 1998; McFadden and Al Khalili

1999; Shapiro 1997)

As

Hall later wrote, "Adaptive

mutations are mutations that occur in nondividing or slowly dividing cells

during prolonged nonlethal selection, and that appear to be specific to the

challenge of the selection in the sense that the only mutations that arise

are those that provide a growth advantage to the cell. The issue of the

specificity has been controversial because it violates our most basic

assumptions about the randomness of mutations with respect to their effect

on the cell." (Hall 1997) 8

In

short, Hall did in fact delete the lacZ gene (as well as other lac

genes with other related functions) in E. coli bacteria.

These mutant bacteria then evolved the ability to use lactose over a very

short period of time in a non-lethal lactose enriched environment.

They were able to do this with the use of a very fortuitous "spare tire" gene (ebg)

that, with a single point mutation, was able to achieve enough lactase activity

to give the cell a selective survival/reproductive advantage (a second mutation was also required in

the promoter region, but this will be discussed in more detail below).

What

are the Odds?

What are the odds?! That is the real question here. What is the

likelihood that some portion of the collective E. coli genome in a

particular colony of 10 billion would be so close to producing a protein

structure with a particular function, or

any other beneficial function at an equivalent level of functional complexity?

How often would this happen? - on average? Would different types of

functions require different minimum sequence size or degrees of specificity with

regard the the specific arrangement of the amino acid residue

"parts"? If so, would greater minimum size and/or specificity

requirements result in differences in the likely gap distance between what

exists in a genome and what might be beneficial if it were ever found via a

random search through the vast potential of sequence space?

In order to begin answering this question, it might be a good idea to take a

closer look at the actual genetic sequences involved with this experiment.

The lacZ gene is quite long. It consists of approximately 3,500

base pairs in the DNA molecule. This gene codes for a protein that is also

fairly long for proteins (~ 1,000 amino acids). This protein then combines

with three other identical proteins to form a large "tetramer" protein of

approximately 4,000 amino acids (see illustration).4 The

complexity of this lacZ gene would seem to be quite evident. The

level of size and apparent complexity of the ebg gene is similar.

In order to begin answering this question, it might be a good idea to take a

closer look at the actual genetic sequences involved with this experiment.

The lacZ gene is quite long. It consists of approximately 3,500

base pairs in the DNA molecule. This gene codes for a protein that is also

fairly long for proteins (~ 1,000 amino acids). This protein then combines

with three other identical proteins to form a large "tetramer" protein of

approximately 4,000 amino acids (see illustration).4 The

complexity of this lacZ gene would seem to be quite evident. The

level of size and apparent complexity of the ebg gene is similar.

Appearances

can be deceiving though. Maybe lactose hydrolysis is not really as

complicated as the size of this gene makes it appear? As it turns out, a BLAST

search through the known protein databases quickly shows that the smallest known

functional lactase enzyme in any creature is about 380 amino acid residues in size.

Some of these residues also seem to carry with them a fair degree of sequence

specificity. However, many of the residue positions can change, and some of them

can change dramatically, without a significant loss of lactase function.

But, overall, the changeability of the lactase enzyme is at least moderately limited.

Some have suggested to me that there are around 10100 potential

lactase enzymes in all of sequence space made up of chains of proteins

containing 380 residues. Although 10100 does sound like an

absolutely huge number (only 1080 total atoms in the entire

universe), it is actually rather tiny when compared to the total

size of sequence space (~10494 possible combinations for a string of just

380 amino acid residues). With this ratio, for every 1 lactase enzyme, there are

about 10394 non-lactase sequences.

A

Game of Checkers

The

potential of "sequence space" can be visualized as a

gigantic checkerboard. Each square on the checkerboard represents a

different amino acid residue sequence. Each member of a population can

only occupy one square at a time (though any one square may be occupied by many

individuals at any one time). A limited population simply cannot cover all

the potential squares on the checkerboard at any given moment of time.

With each mutation to an individual, it changes squares. If any one

individual comes across a beneficial sequence square, like a residues sequence

with the lactase enzyme function while in a lactose rich environment, that individual and its offspring will tend to stay on that square

because of the selective advantage given by that square in a lactose rich

environment. This advantage will be translated into increased population

numbers that are on and immediately around that particular square of the

checkerboard. Eventually, in a steady state population, the entire

population will be around that one square because they will all be descendants

of the original individual that first came across that beneficial square on the

checkerboard.

The

potential of "sequence space" can be visualized as a

gigantic checkerboard. Each square on the checkerboard represents a

different amino acid residue sequence. Each member of a population can

only occupy one square at a time (though any one square may be occupied by many

individuals at any one time). A limited population simply cannot cover all

the potential squares on the checkerboard at any given moment of time.

With each mutation to an individual, it changes squares. If any one

individual comes across a beneficial sequence square, like a residues sequence

with the lactase enzyme function while in a lactose rich environment, that individual and its offspring will tend to stay on that square

because of the selective advantage given by that square in a lactose rich

environment. This advantage will be translated into increased population

numbers that are on and immediately around that particular square of the

checkerboard. Eventually, in a steady state population, the entire

population will be around that one square because they will all be descendants

of the original individual that first came across that beneficial square on the

checkerboard.

The

problem is that not every square is beneficial. Depending upon the level

of functional complexity in question, most squares are completely neutral for

survival and many more are detrimental. So, in traveling from one

beneficial square to another beneficial square at the same level or even a higher enzymatic level of

complexity, an open ocean of non-beneficial sequences will have to be crossed.

The problem with this open ocean is that during this voyage over neutral waters,

natural selection cannot direct the process at all. Nature is blind to

such voyages and so the process becomes purely random. In fact, this

voyage has a mathematical name called "random walk" which does in fact

occur in real life (i.e., Kimura's Neutral Theory of Evolution).

The

problem is that not every square is beneficial. Depending upon the level

of functional complexity in question, most squares are completely neutral for

survival and many more are detrimental. So, in traveling from one

beneficial square to another beneficial square at the same level or even a higher enzymatic level of

complexity, an open ocean of non-beneficial sequences will have to be crossed.

The problem with this open ocean is that during this voyage over neutral waters,

natural selection cannot direct the process at all. Nature is blind to

such voyages and so the process becomes purely random. In fact, this

voyage has a mathematical name called "random walk" which does in fact

occur in real life (i.e., Kimura's Neutral Theory of Evolution).

The

interesting thing about random walk is that with each doubling of the distance

length to the average beneficial sequence square on our checkerboard, the time

involved increases exponentially. For example, if the average random

walk required for a particular colony of bacteria to achieve a particular level

of complexity required 5 neutral steps or changes in DNA, the total number of

options or potential spaces on our checkerboard between the starting point and a

new "winning" square would be 4 (remember that there are four

potential bases that can fill one given location in a string of DNA) to the

power of 5, or 1,024 squares. So, the random walk would not simply take 5 steps

in a straight line to the new beneficial square. Not at all. The

random walk would wander randomly or blindly around 1,024 squares, taking far

more steps, on average, to find the one square out of 1,024 that is actually

selectable as "beneficial" to those that are searching the sequence

space of that checkerboard. Depending

on our population's size and mutation rate, we could estimate an average time

required to reach all of these squares at least once beginning at a given starting point. Obviously though, the bigger the population and the higher

the mutation rate, the faster random walk could reach all of the squares.

For

instance, if we started out with a population of 1 trillion bacteria and if all

of these bacteria started out on one square on our checkerboard, it would take

around 65,000 generations (if each individual sequence of a given length was

mutated at least once in each generation) for them to reach equilibrium over all

the squares of the checkerboard - kind of like a tall column of sand being let

loose at one location and then rapidly flowing and spreading itself in all

directions to other locations. At equilibrium (i.e., when the pile of sand

becomes perfectly "flat" or evenly distributed over all surfaces),

about 0.098% of the bacteria will be on each one of the 1,024 squares of the

checkerboard. Even though 0.098% does not really seem like a big number,

it actually works out to be around 9.8 billion out of a population of 1

trillion. In other words, after about 65,000 generations, there would be

an average of 9.8 billion bacteria covering each one of the 1,024 squares on our

checkerboard of potential space.

So

obviously, a gap of 5 neutral mutations would not be a problem for a population

of 1 trillion bacteria to cross in relatively short order. But, what

happens if we double the gap to 10? A gap of 10 neutral mutations/steps

would create a checkerboard with over 1 million squares of potential space

(1,048,576 to be exact). At equilibrium, our population of 1 trillion

would have only 953,674 individuals on each of the squares instead of the 98

billion it had when the gap averaged only 5 steps wide. Doubling the gap

again to 20 steps makes our checkerboard grow a million fold to just over 1

trillion squares of potential space (1,099,511,627,776). Now, our

population of 1 trillion would average a bit less than one member of the

population on any one square at any given point in time. I think the trend

is obvious by now, but just for kicks, doubling the gap again to 40 steps

increases the size of our checkerboard a trillion fold to just over 1 trillion

trillion squares. Now, at equilibrium, each one of the members of our

population of one trillion are surrounded, on average, by one trillion empty

squares that they have to search out all by themselves.

Average

Time

Take

a population of bacteria the size of all the bacteria that currently exist on

the entire Earth - about 1e30 bacteria. Let's say that this steady state

population produces a new generation at a rate of 20 minutes and has a mutation

rate of 1e-8 per codon position - given a genome per bacterium of 10 million

codons. How long would it take such a population to find a new beneficial

function at the level of 1,000 fairly specified residues?

Well,

first we have to calculate the likely gap size. Using an average between

the calculations of Yockey and Sauer, the ratio of potential beneficial vs.

non-beneficial for 100aa systems is about 1e-40.13,14,15 This

creates a ratio for a 1,000aa system of about 1e-40(1000/100) =

1e-400. So, the average gap size between potentially beneficial sequences at

this level would be about 308 residue differences - i.e., 20308

= 1e400.

At

his point, one can calculate the Poisson

distribution curve to determine the odds that any particular gap would exist

(given the average gap of 308 residue differences). Although extremely unlikely

given the Poisson distribution, let's say that our colony has a few closer

sequences that just aren't "average" - close enough to be only 50

specific residue changes away from at least one beneficial function at this

level of minimum size and specificity. How long would it take to get just

50 specific residue changes?

A

gap of 50 specific residue differences from a given 1,000aa sequence means that

each of these sequences is surrounded by 1e65 non-beneficial options. But,

we have 1e30 bacteria with 1e7 codons each. For arguments sake, lets say

that each bacterium has 1e5 sequences of 1,000 codons that are within 50 residue

changes of success. This gives us a total population of 1e35 starting

points that are within 50 changes of success.

Now,

how long will it take to get these 50 needed changes in at least one bacterium

in our population? After equilibrium of distribution randomly through

sequence space is realized, each one of our starting point sequences must search

through a sequence space of 1e65/1e35 = ~1e30 sequences, on average, before

success will be realized. With a mutation rate of 1e-8 per codon per

generation our 1,000-codon sequence will get mutated once every 1e5 generations.

With a generation time of 20 minutes one mutational step takes about

2,000,000 minutes or approximately 4 years. So, with one random walk step every

4 years, it would take 1e30 * 4 = 4e30 years to achieve success - on average

(i.e., trillions upon trillions of years).

Evolution

Stalling Out

With each doubling of the

likely neutral

gap, the average time required for "success" increases exponentially. Of course, one way to reduce the

average required time is to increase the

population's size exponentially. This does help for a while, but very

quickly the required size of the population becomes impractical for any

environment to support and further evolution simply stalls out, in an

exponential manner, with attempts to reach higher and higher levels of

functional complexity. Interestingly

enough, Barry Hall discusses this very problem:

Given

a gene of 1000 base pairs there are over 1034 sequences that differ

from the wild-type sequences by 10 or fewer mutations. Not only can we not

explore all of those possible variants, life itself has barely had sufficient

time to explore all of those possibilities. The mass of the earth's oceans is

about 1.4 x 1024g. Even if living cells constituted a 10-4

of the mass of the oceans, given about 1012 bacterial cells per

gram, a reproduction rate of about 1 cell generation per day and a mutation

rate of about 10-9 per cell generation and 4 billion years of life

there has been sufficient time to explore only 1.6 x 1034 variants

of a single 1000-bp sequence. However, evolution does not proceed by exploring

all possible variants but by incorporating single mutations, selecting the

fittest of those variants, expanding the population of the fittest variants,

and incorporating additional single changes.

Hall

goes on to explain: If the evolved sequence differs from the

wild-type at n sites there are n possible first-step amino acid replacement

mutants. Each of those single mutants can be created by site directed

mutagenesis and the effect on fitness determined by competition experiments.

The best (fittest) of those amino acid replacements can be chosen and the n31

possible second-step mutants created, the fittest double mutant chosen, the

n32 possible third-step mutations introduced, etc. The effect of this exercise

is to mimic an evolutionary pathway in which the fittest single mutant is

fixed into the population, that population expands, the fittest double mutant

arises and is fixed into the population, etc. Orr has recently shown on

theoretical grounds that adaptive evolution is expected to proceed in exactly

this fashion in which the first mutations to be fixed are those that have the

greatest positive effect. 9

Of

course, all of Hall's single steps here are functionally beneficial. What

happens if there are true gaps in function? What happens to evolution? Hall

continues:

If

that sequence involves six amino acid replacements, we might find that after

introducing three replacements, each of which further improves fitness, none

of the three remaining replacements improves fitness. Assuming that the final

six-mutant sequence is significantly fitter than the triple mutant, that

result means that two, or perhaps even three, of the remaining substitutions

must be introduced simultaneously to further improve fitness. This

simultaneous occurrence of two or more specific mutations is obviously highly

unlikely, but what about the possibility that one of the two mutations will

arise, by selectively neutral, but be fixed into the population by drift? Were

that to occur the second mutation would quickly be incorporated by selection.

The probability that a newly arisen neutral mutation will be fixed into the

population is the reciprocal of the population size. When populations are

large enough that the probability of the occurrence of the mutation is very

high, e.g., the population size approaches the reciprocal of the spontaneous

mutation rate, then the probability of the fixation is very low. Although

neutral variants arise constantly, it is very unlikely that the particular

neutral variant we require will be fixed into the population. Thus, unless

each of the mutations confers a selective advantage relative to its parent, it

is unlikely that the final six-mutant sequence would evolve naturally. In the

example above we would conclude that the evolutionary potential may well be

limited to the triple mutant. 9

So, even Hall admits that very small neutral gaps of three mutations might

be enough to "limit" further evolution. Thus, such functions that are

isolated from other functions by neutral gaps might be quite difficult for a

theory based on the mechanism of random mutation and function-based

"natural" selection to explain.

Humpty

Dumpty Had a Great Fall

What

is also most interesting is that the same bacteria that couldn't evolve a

relatively simple single protein enzymatic function, like lactase (i.e., Hall's

double mutant E. coli), would quickly evolve

resistance to any modern antibiotic in short order via random mutation and

natural selection. Why then is it so easy to evolve antibiotic

resistance but not a beneficial enzyme starting with what is currently

available in the collective genome? Well, perhaps it is because functions

are not created equal. Some functions are extremely simple while others

are vastly more complex (i.e., in both the minimum length requirement of a coded

sequence or number of required parts as well as the minimum degree of specified

arrangement of the sequence or types of parts).

De novo antibiotic

resistance is one of the most simple functions around. The reason for this

can be found in the specificity of a given antibiotic for a particular target

within a bacterium. Because of this high specificity, there is a

very high ratio of potentially "beneficial" changes compared to

"non-beneficial" changes that can in fact interfere with such specific

interactions of molecules. The neutral gap involved in finding at least

one of these very common potential interfering sequences is quite small indeed.

Perhaps, in some cases, a majority of mutations would result in interference

with such a specific interaction. Obviously then, when an interfering

mutation does come along that blocks or completely destroys the interaction of

an antibiotic with its specified target, the antibiotic resistance function is

evolved. It is much like the breaking of Humpty Dumpty when he fell off

the wall. He broke easily because there are so many ways he could be

"broken". However, it wasn't so easy to put him back together

again because the vast majority of potential ways to arrange his parts just

won't "work" - and that's the catch for the theory of evolution.

Functions

that are based on the destruction or interference with other pre-formed

functions or interactions are universally very simple to evolve. This is

mathematically predictable and in real life it does in fact occur quite

commonly. Antibiotic resistance evolves very rapidly in real life even

without access to such complex antibiotic enzymes like penicillinase (which has

never been shown to evolve in real time by the way). A few other types of

drug resistance, such as chloroquine resistance, have taken a bit longer to

evolve in real life (though never in laboratory conditions), but even this type

of evolution works on the same basis of interference with a preformed function.

Chloroquine

resistance (CQR) seems to require at least a few mutations (as many as 6, but

perhaps only two mutations), before at least some beneficial level of resistance

can be realized. It turns out that several of the mutations seen in CQR are

selectively advantageous once the initial two or three are realized.

Resistance to both mefloquine and chloroquine is achieved via the blocking of or

interference with a pre-established interaction of these drugs with specific

target proteins.

Again,

the prediction that such interferences are relatively easy to achieve holds up

in these cases as well. No new protein or enzyme is evolved in these cases. The

only thing that happens is a disruption of a specific interaction that was

pre-established. It is just a different way of breaking Humpty Dumpty, but

still relatively easy to do with large populations. This evidence fits very well

with my predictions for the required time needed to evolve functions at this very low level

of complexity (more of the details of chloroquine resistance in the reference section below).10

Climbing

the Ladder of Functional Complexity

However,

as one moves up the ladder of complexity to those functions that are not based

on interference with pre-established functions (single protein enzymes like

lactase, nylonase, penicillinase, etc), the relative number of such

sequences is dramatically reduced. This makes the evolution of such

functions much more

difficult and, in real life, there are far fewer examples at this level of

functional complexity. Certainly the evolution of lactase, nylonase,

and several other single protein enzymes that have been demonstrated in real

life are definite examples of higher-order evolution in action when compared to

the extremely simple function of antibiotic resistance and other such functions. However,

there are far fewer examples at this level, relatively speaking, And, there are

very interesting limitations at this level - as illustrated in Hall's

experiments with lactase evolution in E. coli.

Evidence

for this position can be found in the fact that all bacteria can and do rapidly

evolve antibiotic resistance to any antibiotic that is brought their way.

However, only a very few of them can evolve new enzymatic activities, such as a

relatively simple lactase function provided by any one of literally trillions

upon trillions of potential lactase enzymes dispersed through sequence

space.

Of

course, there are even higher levels of complexity that involve multiple

proteins all working together at the same time in order for a particular

function to be realized. A classic example of such a level of function can

be found in bacterial

motility systems. All bacterial motility systems are dependent upon

the simultaneous action of many different proteins all working together

in harmony in specific orientation with each other. A common example of such a motility system is the flagellar

system of motility. The flagellar system requires around 50 genes to

construct and regulate the eubacterial flagellum and around around 18-20 fairly specified

proteins (averaging around 300 residues each), to form the actual motor-switch-shaft-propeller complex.

Of

course, there are even higher levels of complexity that involve multiple

proteins all working together at the same time in order for a particular

function to be realized. A classic example of such a level of function can

be found in bacterial

motility systems. All bacterial motility systems are dependent upon

the simultaneous action of many different proteins all working together

in harmony in specific orientation with each other. A common example of such a motility system is the flagellar

system of motility. The flagellar system requires around 50 genes to

construct and regulate the eubacterial flagellum and around around 18-20 fairly specified

proteins (averaging around 300 residues each), to form the actual motor-switch-shaft-propeller complex.

![]() The

flagellum is in fact a biochemical machine that does very much resemble

something a human would design. There is the helical filament (propeller),

the hook (universal joint), the rod (drive shaft), the S-P ring (bushing around

the rod - in gram negative bacteria), the SMC ring complex, and the

"motor" which includes the stator and the rotor. The entire assembly

is hollow, including the actual filament. The rotor, hook and filament are made

of different helical proteins that self assemble to form hollow, cylindrical

structures (in the case of the filament, the cylinder is helical so that it acts

as a "screw propeller" when it rotates. Also, many eubacteria

can switch the direction of rotation of the propeller (and hence the direction

of travel) and the "switch" mechanism appears to be part of the

motor complex (More detail is listed below in

the reference section as well as in another essay of mine dealing specifically with the flagellum).

1, 11

The

flagellum is in fact a biochemical machine that does very much resemble

something a human would design. There is the helical filament (propeller),

the hook (universal joint), the rod (drive shaft), the S-P ring (bushing around

the rod - in gram negative bacteria), the SMC ring complex, and the

"motor" which includes the stator and the rotor. The entire assembly

is hollow, including the actual filament. The rotor, hook and filament are made

of different helical proteins that self assemble to form hollow, cylindrical

structures (in the case of the filament, the cylinder is helical so that it acts

as a "screw propeller" when it rotates. Also, many eubacteria

can switch the direction of rotation of the propeller (and hence the direction

of travel) and the "switch" mechanism appears to be part of the

motor complex (More detail is listed below in

the reference section as well as in another essay of mine dealing specifically with the flagellum).

1, 11

Minimum

Number and Specificity of Parts

Without

a minimum number of parts being present in the proper "specified"

order and orientation, the function of motility could not be realized, even a

little bit. Many, like biologist Kenneth Miller, argue that such multi-part systems of function are made up of

less complex sub-systems of function that have other functions within the cell -

meaning that they are not truly "irreducibly complex".

The argument is made that several of the flagellar sub-structural proteins and

even systems of protein parts have homologues in other independently functional

cellular systems. One well-known example is a secretory system called the

"Type III protein secretion system" or "TTSS". Interestingly enough, some

of the parts used in the secretory systems of some species are nearly identical

to some of the parts used in the flagellar motility system (More detail

in reference section and flagellum

paper).11 Of course, the object of such

arguments is to suggest that as long as all the needed sub-parts are there, that

a beneficial apparatus of higher functional complexity, like the flagellar

motility system, will obviously self-assemble, eventually, when needed.

There

are several potential problems with this hypothesis however. Perhaps the

most obvious problem is the fact that no such demonstrations of the evolution of

multiprotein systems of function have ever been observed or even theorized in a

falsifiable way when they require more than a few hundred fairly specified amino

acids working together at the same time (i.e., the multiprotein flagellar system

of motility requires a minimum of several thousand specifically arranged amino

acid residues, working together at the same time). Lower

levels of functional complexity, that involve interference with pre-established

functions (antibiotic resistance) or that are based on single protein enzymes

(lactase, nylonase, etc), have been shown to spontaneously evolve.

However, no function at a higher level of complexity, that involves multiple

proteins totaling more than a few hundred fairly specified residues, has ever

been shown to evolve in real time. There isn't a single published example.

It is here that Behe is

correct in saying that no such system of function has been or likely can be

explained through evolutionary mechanisms of "random mutation combined with

natural selection".

Also,

just because all the necessary parts are available, in close proximity, to form

a potentially beneficial system does not mean that the parts will

"know" how to spontaneously self-assemble to form such a beneficial

system if each intermediate step is not also more "beneficial" than

that which came before. And, we know that the intermediate steps are not

all beneficial when in comes to the functional systems of living things.

In fact, we know that the large majority of all potential changes to both

functional as well as non-functional DNA are neutral at best and, if functional,

are almost always detrimental. This becomes more and more true at higher

and higher levels of functional complexity due to the exponential growth of

neutral gaps with each step up the ladder of functional complexity.

All

Functions are "Irreducibly Complex"

The

fact is that all cellular functions are irreducibly complex in that all

of them require a minimum number of parts in a particular order or orientation.

I go beyond what Behe proposes and make the suggestion that even single-protein

enzymes are irreducibly complex. A minimum number of parts in the form of

amino acid residues are required for them to have their particular functions. The

lactase function cannot be realized in even the smallest degree with a string of

only 5 or 10 or even 100 residues of any arrangement. Also, not only is a

minimum number of parts required for the lactase function to be realized,

but the

parts themselves, once they are available in the proper number, must be

assembled in the proper order and three-dimensional orientation. Brought

together randomly, the residues, if left to themselves, do not know how to

self-assemble themselves to form a much of anything as far as a functional

system that even comes close to the level of complexity of a even a relatively

simple function like a lactase enzyme. And yet, their specified assembly

and ultimate order is vital to function.

Of

course, such relatively simply systems, though truly irreducibly complex, have

evolved. This is because the sequence space at such relatively low levels

of functional complexity is fairly dense. It is fairly easy to come across

new beneficial sequences if the density of potentially beneficial sequences in

sequence space is relatively high. This density does in fact get higher and higher at

lower and lower levels of functional complexity - in an exponential manner.

It is much like

moving between 3-letter words in the English language system. Since the ratio of meaningful vs. meaningless

3-letter words in the English language is somewhere around 1:18, one can

randomly find a new meaningful and even beneficial 3-letter word via single random

letter changes/mutations in relatively short order. This is not true for

those ideas/functions/meanings that require more and more letters. For

example, the ratio of meaningful vs. meaningless 7-letter words and combinations

of smaller words equaling 7-letters is far far lower at about 1 in 250,000.

It is therefore just a bit harder to evolve between 7-letter words, one mutation

at a time, than it was to evolve between 3-letter words owing to the exponential

decline in the ratio of meaningful vs. meaningless sequences.

The

same thing is true for the evolution of codes, information systems, and systems

of function in living things as it is for non-living things (i.e., computer

systems etc). The parts of these codes and systems of function, if

brought together randomly, simply do not have enough meaningful information to

do much of anything. So, how are they brought together in living things to form

such high level functional order?

Limited

Evolutionary Potential

And yet, despite these many problems, professors Hall and Miller and many other

scientists like them would have us believe that the evolution of even more

complex functions than single protein enzymes is still a relatively simple or at

least a doable process given a few million or even billion years. Such

conclusions might be a bit premature to say the least since many of Hall's

mutant E. coli seemed to have more than a little difficulty evolving just

one relatively simple single-protein enzymatic function. Hall himself

described these strains as having "limited evolutionary potential." 3

Hall noted that with both the lacZ and the ebg genes missing, E.

coli bacteria cannot evolve lactase ability at all despite his own efforts

and those of several others, such as J. H. Campbell, to test for and observe

such evolution over the course of many years (since 1973) totaling hundreds of

thousands of bacterial generations.6

Hall did seem to realize somewhat of the implications of discovering that only

one mutation was needed to "evolve" efficient lactase activity in lacZ

negative E. coli strains. In his paper he said, "The realization

that a single mutation in ebgA [ebg =

evolved b-galactosidase gene] was sufficient to convert ebg0 enzyme

into an efficient lactase was therefore disappointing." 3

The problem, as Hall himself pointed out, is that there are

mutations that do not yield changes in protein function toward anything useful

to the cell. The proteins that result from these mutations might in fact

be useful to another organism somewhere in the universe, but for the particular

organism that they have evolved in, they are either neutral in function or

nonfunctional . . . or, even worse, detrimental in function.

No cell or organism or even an entire gene pool has an infinite vocabulary.

All living things have limited individual vocabularies. Out of the huge

number of possibilities for different kinds of proteins of a given length, any

one individual cell or gene pool of cells "recognizes" or can use only

a small fraction of them in a beneficial way (and this fraction gets

exponentially smaller as the level of complexity increases). Therefore,

some functions are in fact out of statistical reach for that particular cell, or

gene pool of cells, as well as their offspring because they do not recognize, as

beneficial, any change in the functions of intermediary proteins along the way

toward those sequences that would in fact be beneficial. Such neutral

evolution looses the guidance of natural selection as a driving force.

Hall describes such evolutionarily-challenged bacterial strains as having "limited evolutionary potential." I propose that every living creature

has very limited evolutionary potential.

Bridges

Between Old and New Functions

Some might argue that some

of the changes described by Hall did in fact cross bridges of non-function.

This is true. Hall described the crossing a nonfunctional bridge that was

two mutations wide. Hall found even this challenge statistically unlikely,

but it did in fact happen experimentally. The statistical problem Hall

describes is that for each genetic change in function, a change in regulator

function is also needed. A regulator is needed to control the production

of the regulated gene. Without regulation, genetic products are not

advantageous and will be selected against in later generations. The needed

lactase regulator change also required, in this case, a single point mutation

that was in line with the single lactase gene point mutation.

Independently, the statistical odds of the needed genetic mutation happening in

a given bacterium, according to Hall, was 2 x 10-9 and the

statistical odds for the needed mutation in the regulator region of that gene is

1 x 10-8 (at best). The generation time for Hall's bacterial

cultures averaged 6 hours and the average number of bacteria that were being

studied at any given steady state was at best 1010 cells.

According to Hall's own statistical calculations, the average time required

for both of these needed mutations to occur in any one of his bacterial colonies

was on the order of 100,000 years.

It seems though that Hall's math was a bit off. According to the

statistics of random walk in a population of 10 billion, a gap of two mutations

(only 16 squares to cover on our checkerboard) would be crossed in short order -

and it was crossed in short order. According to Hall, colonies containing

both of these mutations were isolated in as little as nine days. However,

because of Hall's calculations (based on the requirement of full fixation of the

first "correct" mutation in the colony before a gain of the second

"correct" mutation) and estimates of much more time to achieve such a

crossing, Hall concluded that, "under some conditions spontaneous mutations

are not independent events." He went on to say that this is

"heresy, I am aware." 3

Because of his statistical

calculations, Hall was forced to conclude that mutations are not always random

events but that sometimes point mutations occur in tandem at a higher rate than

random chance alone would allow. Of course there was no logical

explanation for this assumption, and yet Hall assumed that was is in fact what

was happening. He felt forced to conclude that nature seems to know what

it wants ahead of time and manipulates mutations without the aid of any

functional advantage. Truly, this is scientific heresy as Hall indicates.

It is basically a statement of magic. Of course, Hall was wrong.

Random walk in such a large bacterial population can easily cross a gap of 2 or

3 or several more mutations in very short order, but what is there that explains

the existence of gaps that average hundreds, thousands, or even millions of

mutations wide? Magic? - or intelligent design?

Statistical

Road Kill

Miller and Hall have failed to defeat Behe's argument of irreducible complexity

for one simple reason that Behe describes as statistical "road kill."

As previously described, the road-kill problem is the problem of gaps - gaps of

neutral function. Single point mutations quickly come to gaps of neutral

or even non-function that require multiple mutations to cross. At this

point, evolution is stuck. And yet, we know that these gaps have in fact

been crossed somehow, but how? Obviously something or someone has crossed

them at some point, because genes do in fact exist on the other side of these

gaps. The gaps themselves exclude natural selection as a force that can

fly evolution over to the other side since natural selection is dependent upon

the detection of functional phenotypic change. Without natural selection,

the crossing of these gaps via any naturalistic process remains a mystery.

Random mutation, by itself, tends toward homogeny, not the increase of meaningful

genetic information. Therefore, without guidance, random chance fails as a

creative force of new high-level systems of function because random chance

eventually creates homogeny (i.e., goop).

However, if it is still difficult to see that neutral genetic gaps significantly

limit the powers of Darwinian evolution, consider the Shakespearean phrase,

"Methinks it is like a weasel" used by Richard Dawkins to illustrate the

power of natural selection.12 Try and change any one letter or

space and still have the sentence remain meaningful as well as beneficial in a

given situation/environment. You might change it to read, "Me thinks it

is like a weasel" then, "He thinks it is like a weasel." It still

makes sense and it means something different. Aha! Evolution in

action. Keep going though. How far can you evolve this sentence

where each and every character change remains meaningful much less beneficial?

You might mutate it to, "She thinks it is like a weasel" then, "She thinks

it is like a teasel" then, "She thinks it is like a tease" then,

"He

thinks it is like a tease" then… well… you see, it is getting quite

difficult to keep evolving unique as well as meaningful phrases one mutation at

a time. We run into evolutionary dead

ends really fast.

The same problem happens with genetic "evolution." The genetic

blueprints of living things are written according to very specific rules of

"grammar." The order or sequencing of genes is very important to

function. Not just any order will do. The "spelling" of genetic

words also matters. The cell will not recognize just any spelling as

beneficial in a given environment. So, to go from one functional genetic

phrase to another uniquely functional genetic phrase in a higher level of

functional complexity might be a bit of a problem if such changes require the

crossing of even a few neutral or detrimental steps of random walk.

Each mutation that does not cause a beneficial change in function (i.e., neutral

or detrimental) is one lane in the statistical highway that Behe describes.

The blind turtle of evolution must cross this highway to reach the new

beneficial function. With each additional lane added to the highway, the

average time needed for the blind turtle to make it across increases

exponentially. Each lane that is added skyrockets the average needed time

for success until 4 or 5 billion years pales into the distance of trillions upon

trillions of years.

Given

Enough Time Anything is Possible

There are those who say that evolution is improbable, but that time makes the

improbable - probable. Time becomes the savior of evolution. This

might be true except for one small problem. Evolution needs more time than the

history of the universe, or even millions upon billions upon trillions of

universes have to offer - on average. How high do the odds have to go

before we suspect that all this just isn't the result of any non-deliberate

process? How many times would the same person be able to win the

California Lottery in a row before one could reasonably suspect the possibility

of deliberate cheating?

-

Behe,

Michael J. Darwin's Black Box,

The Free Press, 1996.

-

Miller,

Kenneth R., Finding Darwin’s God,

HarperCollins Publishers, 1999.

-

B.G.

Hall, Evolution on a Petri Dish. The

Evolved Beta-Galactosidase System as a Model for Studying Acquisitive Evolution

in the Laboratory, Evolutionary Biology, 15(1982): 85-150.

-

Lewin,

Benjamin, Genes V, Oxford

University Press, 1994.

-

Levinson,

Warren E. et al., Medical

Microbiology and Immunology 3rd Ed., Appleton & Lange,

1994.

-

Campbel,

J.H., Lengyel, J., and Langridge, J., 1973, Evolution of a second gene for

B-galactosidase in Escherichia coli, proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA

70:1841-1845.

-

Behe,

Michael J., Irreducible Complexity and the Evolutionary Literature:

Response to Critics, Discovery Institute, July 2001. (http://www.arn.org/docs/behe/mb_evolutionaryliterature.htm)

-

Behe,

Michael J., "A True Acid Test" - Response to Kenneth Miller,

Discovery Institute, May 2002.

(http://www.trueorigin.org/behe02.asp)

-

Hall,

Barry G., Toward and Understanding of Evolutionary Potential, FEMS

Microbiology Letters 178 (1999) 1-6, June 1999. (http://www.eeb.uconn.edu/Courses/EEB449/Hall%20FEMS.pdf)

-

Jane

MR Carlton, David A Fidock, Abdoulaye Djimdé,Christopher V Plowe and Thomas

E Wellems, Conservation of a novel vacuolar transporter in Plasmodium

species and its central role in chloroquine

resistance of P. falciparum, Current

Opinion in Microbiology, 2001. (http://www.dbbm.fiocruz.br/class/Lecture/d24/drug_resistance/mc4404.pdf)

In

human red blood cells, Plasmodium falciparum (the malaria

parasite) supports its growth by taking up host cell cytoplasm in an acidic

digestive food vacuole. Toxic heme, in its hematin form, is released in the

vacuole by hemoglobin digestion and is crystallized into innocuous hemozoin,

or "malaria pigment". Chloroquine (CQ) interferes with this

process by complexing with hemozoin. This complex prevents hematin from

crystallizing into the innocuous hemozoin form. The "toxic"

effects of free hematin are caused by hematin's ability to increase membrane

permeability which lead to cell lysis and death. Hematin also is known to

inhibit parasite enzymes.

Chloroquine

resistant strains of P. falciparum show a reduced accumulation of CQ

in the digestive vacuole. The genetic mutations associated with this reduced

accumulation have been isolated to the PfCRT (P. falciparum

chloroquine resistance transporter) gene. The gene contains 13 exons that

cover 3.1 kb. The PfCRT gene product is a 423 amino acyl ten-transmembrane

channel or transporter protein that catalyzes chloroquine flux and H+

equilibrium across the digestive vacuole membrane. Many different point

mutations have been isolated in resistant CQR strains of malaria (M74I,

N75E, K76T, A220S, Q271E, N326S, I356T, and R371I). Of these, only the K76T

and the A220S mutations are shared in common between resistant malaria

strains on various affected continents of Asia, Africa, and S. America. The

K76T mutation in particular seems to be the most important marker of CQR.

What is interesting is that the K76T mutation is never seen by itself, but

is always associated with a few other point mutations. However, in some CQ

resistance strains the K76T mutation is absent. One such strain is the

"106/1" strain that has the K76I mutation instead. This strain has

six of the other point mutations, but is has the K76I instead of the K76T

mutation at position 76. Even without the K76T mutation the 106/1 strain

does have a fairly high level of CQR. However, the level of resistance is

not as high as those strains that do have the K76T mutation. Interestingly

enough, Fidock et al., performed an experiment with the 106/1 strain where

stepwise CQ pressure was added to the population. The result was a fairly

rapid change at position 76 from the K76I to the more resistant K76T

mutation.

The

results of such observations suggest that the K76T mutation is not

selectively advantageous by itself. the A220S may fulfill a particular

requirement in the development of CQR since this mutation has consistently

been found to accompany the K76T mutation in CQR parasites from the

different New and Old World foci. "The suggestion that K76T cannot

occur in the absence of other PfCRT point mutations may also explain the

slow genesis of CQ resistance in the field as well as the difficulties that

have been experienced with attempts to select CQ resistance in the

laboratory."11

-

Ian Musgrave, Evolution of the Bacterial Flagella, Personal Website, created in

2000. (http://www.health.adelaide.edu.au/Pharm/Musgrave/essays/flagella.htm)

-

Dawkins, Richard. The Blind Watchmaker,

1987.

-

Yockey,

H.P., J Theor Biol, p. 91, 1981

-

Yockey,

H.P., "Information Theory and Molecular Biology", Cambridge

University Press, 1992

-

Sauer,

R.T. , James U Bowie, John F.R. Olson, and Wendall A. Lim, 1989,

'Proceedings of the National Academy of Science's USA 86, 2152-2156. and

1990, March 16, Science, 247; and, Olson and R.T. Sauer, 'Proteins:

Structure, Function and Genetics', 7:306 - 316, 1990.

Appendix

The

Flagellum:

Propeller:

The Filament (propellor) is composed of the proteins FlaA and FlaB.

Deletion of FlaB doesn't seem to do hinder motility too much and deletion of

FlaA results in trucated flagella which still produce some motility, and

have some motility.

Hook/universal

joint: This is formed by FlgE

proteins and possible a few others. There is very limited sequence

similarity between the FlgE's of Salmonella sp. and Heliobacter

sp. (33% identity).

Drive

Shaft: The rod (driveshaft) is

composed of a complex of the proteins FlgG, FlgB, FlgC, FlgF and FliJ, P, Q,

R. The M ring is formed from FliF proteins. The

L and P rings are composed of proteins FlgH, FlgI, but these can be absent

or present without significant effects on flagella function.

Motor:

The motor consists of a rotor (the part that spins) and the stator (the part

that does the spinning). The motor is largely contained by the C ring motor

complex. This is formed from FliG, FliM, FliN proteins which form the

rotor/switch apparatus. The stator is formed from either MotA and B in some

species, and PomA, PomB, MotX and MotY in others .

Stator:

Mot A and B forms a proton pump which provides the power of the motor, MotB

also serves to anchor the motor to the cell. Deletion of Mot A or B paralyses

the cell. FliG and FliM proteins are also involved.

In

Rhodobacter sphaeroides, the genes equivalent to MotA and MotB have

only 19% sequence identity. The Rhodobacter motor doesn't switch as

does the other motors, but turns on and off, and re-orientation is via

Brownian motion.

In

Vibro species, the motor is a sodium, rather than proton pump,

composed of pomA, pomB, MotX and MotY. The MotX and Y proteins are

unrelated to MotA or B, but PomA seems to be related to MotA from R.

spheroides, and R. spheroides. MotA can partially restore

swimming in PomA paralyzed mutants.

The

rotor: The FliG protein is

involved in torque generation. It turns the proton gradient into

rotational motion in a poorly understood way. It may also have a role in

switching. FliM is also involved in switching, but probably not in torque

generation. FliN is probably not involved directly in

either torque generation or switching, and may be a stabilizing protein. In Bacillus

species it is replaced by the protein FliY, which resembles a fusion between

FliM and FliN.

Homologues:

It is true

that homology studies have shown that many of the flagellar proteins are

related to parts of the type III protein secretion system. Some of these

parts are even identical in some bacterial species. FliN is homologous to the

Spa0 and HrcQ protein export proteins in the Salmonella and Pseudomonas

respectively. FliP,Q,R and F proteins are homologous to HrcR,S,T and J

proteins of the Pseudomonas Hrp type III secretory system, and indeed

have homologues in most type III secretory systems.

The

type III secretory system forms a "rivet" structure identical to the

rod and SMC ring complex of the flagellum. Furthermore, the

switching/torque generation system (FliG,FliN/Y), has homologues in virtually

every type III secretory system examined so far. Proteins exported by

this system are shunted through the hollow SMC ring and through the rod to the

outside of the cell. In flagellum assembly, flagellins and hook proteins

are shunted to the outside of the cell via the rod and ring complex. The

proteins attach to the outer rim of the rod and self assemble into a tubular

structure that will become the hook and filament. The flagellar proteins

then pass through this tube as it grows. However, there is no apparent

homologue of the motor (MotAB) in type III secretory systems. Several of

the type III secretory systems have tubular structures attached to the rod.

The Hrp secretion system forms basal ring/rod system with a pilus that

strongly resembles the flagellar system. It is not clear if the Hrp pilus has

any relation to the flagellar filament. However, E. coli has a

filamentous structure attached to one of its type III secretory systems which

has significant similarity to the flagellar filament.

.

Home Page

. Truth,

the Scientific Method, and Evolution

.

Methinks

it is Like a Weasel

. The

Cat and the Hat - The Evolution of Code

.

Maquiziliducks

- The Language of Evolution

. Defining

Evolution

.

The

God of the Gaps

. Rube

Goldberg Machines

.

Evolving

the Irreducible

. Gregor

Mendel

.

Natural

Selection

. Computer

Evolution

.

The

Chicken or the Egg

. Antibiotic

Resistance

.

The

Immune System

. Pseudogenes

.

Genetic

Phylogeny

. Fossils

and DNA

.

DNA

Mutation Rates

. Donkeys,

Horses, Mules and Evolution

.

The

Fossil Record

. The

Geologic Column

.

Early Man

. The

Human Eye

.

Carbon

14 and Tree Ring Dating

. Radiometric

Dating

.

Amino Acid

Racemization Dating

. The

Steppingstone Problem

.

Quotes

from Scientists

. Ancient

Ice

.

Meaningful

Information

. The

Flagellum

.

Harlen Bretz

. Milankovitch

Cycles

Since

June 1, 2002

Michael

Behe, professor of biochemistry at Lehigh University, boldly claims that,

"Molecular evolution is not based on scientific authority.

There is no publication in the scientific literature in prestigious

journals, specialty journals, or books that describe how molecular evolution of

any real, complex, biochemical system either did occur or even might have

occurred. There are assertions that

such evolution occurred, but absolutely none are supported by pertinent

experiments or calculations." 1

Michael

Behe, professor of biochemistry at Lehigh University, boldly claims that,

"Molecular evolution is not based on scientific authority.

There is no publication in the scientific literature in prestigious

journals, specialty journals, or books that describe how molecular evolution of

any real, complex, biochemical system either did occur or even might have

occurred. There are assertions that

such evolution occurred, but absolutely none are supported by pertinent

experiments or calculations." 1 Even so, this really was quite an amazing experiment in that a novel

enzymatic function, which was not present in the entire gene pool prior

random mutation and natural selection, did in fact evolve in real time.

Even so, this really was quite an amazing experiment in that a novel

enzymatic function, which was not present in the entire gene pool prior

random mutation and natural selection, did in fact evolve in real time. In order to begin answering this question, it might be a good idea to take a

closer look at the actual genetic sequences involved with this experiment.

The lacZ gene is quite long. It consists of approximately 3,500

base pairs in the DNA molecule. This gene codes for a protein that is also

fairly long for proteins (~ 1,000 amino acids). This protein then combines

with three other identical proteins to form a large "tetramer" protein of

approximately 4,000 amino acids (see illustration).4 The

complexity of this lacZ gene would seem to be quite evident. The

level of size and apparent complexity of the ebg gene is similar.

In order to begin answering this question, it might be a good idea to take a

closer look at the actual genetic sequences involved with this experiment.

The lacZ gene is quite long. It consists of approximately 3,500

base pairs in the DNA molecule. This gene codes for a protein that is also

fairly long for proteins (~ 1,000 amino acids). This protein then combines

with three other identical proteins to form a large "tetramer" protein of

approximately 4,000 amino acids (see illustration).4 The

complexity of this lacZ gene would seem to be quite evident. The

level of size and apparent complexity of the ebg gene is similar.  The

potential of "sequence space" can be visualized as a

gigantic checkerboard. Each square on the checkerboard represents a

different amino acid residue sequence. Each member of a population can

only occupy one square at a time (though any one square may be occupied by many

individuals at any one time). A limited population simply cannot cover all

the potential squares on the checkerboard at any given moment of time.

With each mutation to an individual, it changes squares. If any one

individual comes across a beneficial sequence square, like a residues sequence

with the lactase enzyme function while in a lactose rich environment, that individual and its offspring will tend to stay on that square

because of the selective advantage given by that square in a lactose rich

environment. This advantage will be translated into increased population

numbers that are on and immediately around that particular square of the

checkerboard. Eventually, in a steady state population, the entire

population will be around that one square because they will all be descendants

of the original individual that first came across that beneficial square on the

checkerboard.

The

potential of "sequence space" can be visualized as a

gigantic checkerboard. Each square on the checkerboard represents a

different amino acid residue sequence. Each member of a population can

only occupy one square at a time (though any one square may be occupied by many

individuals at any one time). A limited population simply cannot cover all

the potential squares on the checkerboard at any given moment of time.

With each mutation to an individual, it changes squares. If any one

individual comes across a beneficial sequence square, like a residues sequence

with the lactase enzyme function while in a lactose rich environment, that individual and its offspring will tend to stay on that square

because of the selective advantage given by that square in a lactose rich

environment. This advantage will be translated into increased population

numbers that are on and immediately around that particular square of the

checkerboard. Eventually, in a steady state population, the entire

population will be around that one square because they will all be descendants

of the original individual that first came across that beneficial square on the

checkerboard.  The

problem is that not every square is beneficial. Depending upon the level

of functional complexity in question, most squares are completely neutral for

survival and many more are detrimental. So, in traveling from one

beneficial square to another beneficial square at the same level or even a higher enzymatic level of

complexity, an open ocean of non-beneficial sequences will have to be crossed.

The problem with this open ocean is that during this voyage over neutral waters,

natural selection cannot direct the process at all. Nature is blind to

such voyages and so the process becomes purely random. In fact, this

voyage has a mathematical name called "random walk" which does in fact

occur in real life (i.e., Kimura's Neutral Theory of Evolution).

The

problem is that not every square is beneficial. Depending upon the level

of functional complexity in question, most squares are completely neutral for

survival and many more are detrimental. So, in traveling from one

beneficial square to another beneficial square at the same level or even a higher enzymatic level of

complexity, an open ocean of non-beneficial sequences will have to be crossed.

The problem with this open ocean is that during this voyage over neutral waters,

natural selection cannot direct the process at all. Nature is blind to

such voyages and so the process becomes purely random. In fact, this

voyage has a mathematical name called "random walk" which does in fact

occur in real life (i.e., Kimura's Neutral Theory of Evolution). Of

course, there are even higher levels of complexity that involve multiple

proteins all working together at the same time in order for a particular

function to be realized. A classic example of such a level of function can

be found in

Of

course, there are even higher levels of complexity that involve multiple

proteins all working together at the same time in order for a particular

function to be realized. A classic example of such a level of function can

be found in