Defining

Evolution

And

its Boundaries

Sean

D. Pitman M.D.

©

September 2006

The

theory of evolution is based on a

very simple and elegant idea. The idea is that all living things have a common

ancestor. The differences between living things that exist today are thought to

be the result of "common

decent with modification" or slight changes over time that have simply

added up over many millions of generations to produce the remarkable variety

that we see today. These modifications are the result of mindless

non-directed random genetic mutations combined with natural selection. Natural selection is able to

select between these randomly produced genetic sequences in such a way that

those sequences with the greatest attached beneficial function provide their

host the the greatest reproductive advantage. In this way, natural

selection, while still mindless or non-intentional, is the non-random part of

evolution. 3,4,5,6

If

the amazing diversity of life forms on this planet arose from the evolutionary

potential of a common ancestor life form, the assumption can be made that all or

nearly all life forms living today have the same potential for future diversity.

If true, this mindless force is a very creative force.

But, how does this mindless force work?

Most

will agree that if living things change over time, they change because their

D.N.A. (deoxyribonucleic acid) changed. The

information contained in the DNA is called the “genotype.â€Â

The expression of this information in the physical form of the creature

is called the “phenotype.†1, 2

DNA is very much like the paper that the blueprint for a house is written

down on. This blueprint is

equivalent to the genotype. The

actual house, once it is built, is equivalent to the phenotype.

The phenotype changes only if the blueprint changes.

The

theory of evolution proposes that all the various blueprints of living things

are descendents of a single common ancestor blueprint.

The diversity of blueprints that exist today is simply the result of

variations on a single theme. If

true, the power of the mindless evolutionary force of nature is truly

astounding. The sheer creativity

and magnificent diversity of nature is enough to make even the most cynical

stand in silent awe. If humankind

could harness this power and speed it up with the aid of our intelligent minds,

the implications for advancement seem unlimited.

The

theory of evolution proposes that all the various blueprints of living things

are descendents of a single common ancestor blueprint.

The diversity of blueprints that exist today is simply the result of

variations on a single theme. If

true, the power of the mindless evolutionary force of nature is truly

astounding. The sheer creativity

and magnificent diversity of nature is enough to make even the most cynical

stand in silent awe. If humankind

could harness this power and speed it up with the aid of our intelligent minds,

the implications for advancement seem unlimited.

How

then does this mindless evolution work? How

does the equivalent of a blueprint for a house change over time to code for

phenotypic structures as diverse as an automobile, a battleship, a skyscraper,

or a screwdriver? Obviously, at least this

degree of diversity is seen in living things in the forms of creatures like bacteria, oak trees, and

elephants. In considering this question perhaps we should begin

with Darwin and what he saw. (Back to Top)

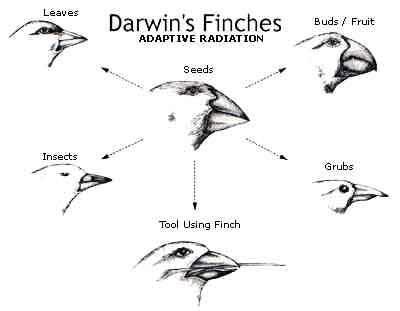

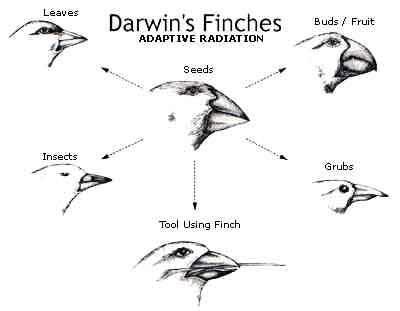

Charles

Darwin

Charles

Darwin (1809-1882) came up with his famous version of the theory of evolution

after observing some very interesting differences, such as the variation in the size

and shape of finch beaks on the Galapagos Islands.

Many other similar changes have also been observed and carefully documented.

Certainly these are “changes†and as changes many would call them

evolutionary changes. If the theory

of evolution is defined as any and every phenotypic change that occurs from

parents to offspring, then it might be perfectly fine to say that finches are

demonstrating evolution in real time. But,

are they demonstrating genotypic evolution?

Has the blueprint changed in an informationally unique way?

Is it possible to have change in phenotype without a change in genotype? In

other words, do the phenotypic changes in the finches that Darwin observed require

new meaningful genetic information that the ancestor finches never had? (Back

to Top)

Gregor

Mendel

Darwin

was unable to answer this question although the answer was in fact available in

his own day. Gregor

Mendel (1822-1884), the father of genetics, came up with the idea of

“alleles†or unchanging “traits†after studying pea plants. 3,7 What

he discovered is that certain phenotypic traits, such a pea color, texture,

shape, and a number of other traits, are passed on by unchanging genotypic

alleles. Different combinations of

these alleles result in different allelic expressions in the phenotype.

Darwin

was unable to answer this question although the answer was in fact available in

his own day. Gregor

Mendel (1822-1884), the father of genetics, came up with the idea of

“alleles†or unchanging “traits†after studying pea plants. 3,7 What

he discovered is that certain phenotypic traits, such a pea color, texture,

shape, and a number of other traits, are passed on by unchanging genotypic

alleles. Different combinations of

these alleles result in different allelic expressions in the phenotype.

For

example, lets say that a house needs colored carpet.

Colored carpet is a “trait†or characteristic of the house listed in

the blueprint. The blueprint of this

particular house is interesting however in that it is a double blueprint.

There are two pieces of paper that code for every aspect of the house. The

two blueprints are identical as far as the traits that they code for (ie:

colored carpet), but they are different as far as the trait variations are

concerned (ie: red, yellow, green, blue or white carpet). If one blueprint

coded for green carpet and the other coded for white carpet, what color would

the carpet be? It will be the “dominant†color.

Mendel

found that allelic traits could be either dominant or recessive (We now know

that they can also be co-dominant, incompletely dominant, additive,

multiplicative etc.) This is made

possible because of the fact that many traits have at least two alleles, or two

separate codes on two blueprint copies, that code for the same trait.

If both alleles are the same, then the expressed phenotype will match

both alleles. If the two alleles

are different, then the phenotypic expression will match the dominant allele.

Each allele is inherited unchanged, one from each parent.

During the process of sexual reproduction, the alleles coding for the

same trait trade places with each other randomly (from one blueprint copy to the

same place on the other blueprint copy) so that the next generation will be

uniquely different from the current generation in their phenotypic expression of

the same alleles. This is why

siblings from the same parents never look exactly alike unless they are twins

arising from the same fertilized egg. Siblings

can in fact look very different from each other and even their parents.

One may have a big nose and the other a small nose.

Similarly, a finch may have a bigger or smaller beak than its siblings.

Such phenotypic changes do indeed occur, but they need not be based in any

change of the common "gene pool" of options. 2

(Back to Top)

Breeding

via Human Selection

The

variation in allelic expression can be quite dramatic.

It is responsible for the majority of changes seen in animal breeding.

For example, the main differences between a Chihuahua and a Great Dane

are primarily the result of trait selection where desired traits contained by a

common gene pool were gathered together over a few generations into one animal.

Most of traits themselves already existed, fully formed, in the common ancestral

gene pool of dogs. Thus, neither of

these breeds has “evolved†much of anything that their common ancestors did

not already have in their common gene pool of options.

The

variation in allelic expression can be quite dramatic.

It is responsible for the majority of changes seen in animal breeding.

For example, the main differences between a Chihuahua and a Great Dane

are primarily the result of trait selection where desired traits contained by a

common gene pool were gathered together over a few generations into one animal.

Most of traits themselves already existed, fully formed, in the common ancestral

gene pool of dogs. Thus, neither of

these breeds has “evolved†much of anything that their common ancestors did

not already have in their common gene pool of options.

The

ability for great phenotypic variation is obvious, but there are clear limits to

this variation. Using genetic

recombination alone, a dog cannot be anything but a dog.

A dog can never be changed, via genetic recombination alone, into a cat

or a chicken or anything else. Why?

Because cats, dogs, and chickens are made from different blueprints that

code for different trait types and trait options that are not contained by the

gene pools of the others. Also, traits that may be similar may not

necessarily be located at the same relative positions on their respective

genetic blueprints.

Again,

using the house blueprint analogy as an example, one house might have a

blueprint that codes for carpet at the bottom right-hand corner of the page.

Another house might have a blueprint that codes for an electric garage door

opener at this location and has no code for carpet at all. Also, the first

house might not have a code for a garage much less an electric garage door

opener. Neither one of the blueprints for one house will match with the

options or order of options for the other house.

So,

what does this mean?

It means that the blueprints for the different houses in this case cannot talk

to each other, mix and match, or "recombine" their collective

information in any functional way. They cannot

"interbreed" so to speak to produce viable "offspring".

Only blueprints that have the same setup and "trait" types can

exchange equivalent information with each other. It is impossible then for

blueprints that do not have a position for a garage code to trade equivalent

information that results in the formation of a garage. The same is true

for different animals such as dogs, chickens and cats. They cannot breed

with each other, nor can they be bred to look like each other, using genetic

recombination alone.

Although

genetic

recombination can and does result in some very dramatic phenotypic changes for

these creatures, this process is limited by the edges of a large

but finite pool of options. Such a

gene pool remains fixed while various creatures within the gene pool give

phenotypic expression to various aspects of this genotypic pool of options.

The pool provides the means for huge phenotypic variation or “changeâ€Â

but the genotypic pool itself may not change from one generation to the next. 8

The changing phenotypic creature is nothing more than a partial

reflection of a non-changing or "static" genotypic pool. Thus,

it is the genotypic pool and not the phenotypic creature that "real" evolution must act

on.

But, if Darwin’s finch

beaks are not examples of gene pool evolution is there anything that is?

Is there any creature that has unique traits that its ancestors did not

have in their gene pool? (Back

to Top)

Random

Mutations

This

is where mutations come into play. Genetic mutations are relatively rare

random changes that occur in a creature's genotypic blueprint that were not in

the blueprints of that creature’s parents.

There are many different types of mutations.

There are point mutations where just one letter is changed in the wording

of the genetic blueprint. There are

translocation mutations where a section of the blueprint is cut out and pasted

in another place on the blueprint. There

are inversion mutations where a section of the blueprint is cut out and turned

upside down and pasted back in the same place.

There are duplication mutations where a section of the blueprint is

copied and then pasted in another place. The

list goes on and on, but basically the mutated blueprint has genes/alleles or

genetic sequences that were not in the blueprints of either one of the parent

blueprints. 1,2,4

(Back to Top)

Functional

vs. Neutral Mutations

As

would seem intuitive, most functional mutations are harmful and may even

be lethal. Fortunately though, most

mutations are not functional. Most mutations are silent or

"neutral" and result in no detectable phenotypic change. Very

rarely, some mutations are “beneficial.â€Â

The ratio of beneficial vs. detrimental mutations is on the order of 1 in 1,000

for certain types of functions (discussed in more detail below).

Common examples of beneficial mutations are those that give bacteria antibiotic

resistance or those that cause sickle cell anemia in people who live where

malaria is prevalent. But how,

exactly, do beneficial mutations achieve their benefits? (Back

to Top)

Antibiotic

Resistance

In

the case of bacterial

antibiotic resistance, certain mutations actually do result in the fairly

sudden creation of new as well as beneficial functions that the

"parent" bacteria did not have in their collective gene pool of

options.

Now,

it should be noted that bacteria are not like dogs, cats, and

chickens, or anything else that uses sex or genetic recombination as a means of

reproduction. Bacteria reproduce themselves by a relatively simple method

of cell division. In other words, all of the offspring of a given

bacterium will be identical with itself as well as with each other. They

are basically clones of each other. Because of this, there are no trait

options to choose from. There is only one copy of the blueprint instead of

the two copies used in sexual recombination. So, there is only one option for

each bacterial "trait." There is no gene "pool" of options

for each trait - so to speak. Of course, many types of bacteria can in fact

laterally exchange genetic information via

plasmids and the like. But, as a general rule of thumb, bacteria do not

undergo genetic recombination. So, for all practical purposes, all bacteria within a given

isolated population are

identical except if a mutational change occurs. Such mutations,

when they do occur, are passed on to all subsequent offspring.

So,

back to the notion of beneficial mutations. They do happen in bacterial

populations all the time. For example,

penicillin resistance is not always gained by the production of the famous

ß-lactamase

enzyme "penicillinase." There are several other ways that

bacteria become resistant to penicillin. A notable example occurs in Streptococcus

pneumoniae bacteria. ß-lactamase

have never been identified in S. pneumoniae and yet they are capable of

penicillin antibiotic resistance due to modification of their penicillin binding

proteins (PBPs). Since PBPs are the natural target of penicillin, many

different point mutations within this target are capable of interfering with the

target-antibiotic interaction. It is this interference that results in

penicillin resistance. And, importantly, this resistance, combined

with what are called "compensatory

mutations", can be achieved without any significant loss of any other

functional system within the bacterium. So, the argument that all

mutations end up producing at least some detectably harmful effect to gain a

beneficial effect simply isn't true.

Other

antibiotics require a specialized transport protein to bring them into the

bacterium. Again, many different point mutations can interfere with the

ability of the transport protein to interact properly with the antibiotic.

This interference results in resistance to this particular antibiotic. Again,

this interference can be gained without any significant functional loss of

the mutant bacteria relative to their peers.

Other

bacteria already make more complex antibiotic enzymes, such as the penicillinase

enzyme. Such enzymes do not evolve in previously susceptible

bacterial populations. There is not a single documented case where the

penicillinase enzyme code has been observed to evolve in a population where it

wasn't already there. The coded sequence or "gene" needed to

produce the penicillinase enzyme was already there or it was gained via lateral

transfer from other bacteria who already had this code (often via plasmids).

The problem is that this coded sequence is usually regulated so that the

penicillinase enzyme is not produced in sufficient enough quantities to protect

the bacterium from high levels of the penicillin antibiotic. Several

different mutations are capable of blocking or interfering with the suppression of penicillinase

production so that much greater quantities can be made, which results in

enhanced penicillin resistance.

Similarly,

Mycobacterium tuberculosis, the cause

of the tuberculosis disease, produces an enzyme that (as well as its other

useful functions) changes the non-harmful antibiotic "isoniazid" into

its active and lethal form. The now

active isoniazid proceeds to kill the Mycobacterium. Several

different mutations are capable of interfering with the isoniazid-enzyme

interaction. And again, this interference results in Mycobacterial resistance

to isoniazid.

To

give another example, the 4-quinolone antibiotics attack the enzyme “DNA

gyrase†inside various bacteria. Again,

several different point mutations are capable of interfering with the gyrase-antibiotic

interaction.9

Perhaps

the most famous and oft quoted example of a beneficial mutation is the point mutation of the hemoglobin

molecule that is seen in people affected by a condition known as sickle cell anemia.

This single point mutation decreases the effective oxygen carrying capacity of

the hemoglobin molecule.

It still carries oxygen, just not as well.

Now, it just so happens that the malarial parasite needs a high oxygen concentration to survive and so

cannot survive in blood with the sickle cell mutation.10 Those

people who have only one of their two blueprint DNA copies affected by this

mutation do not have significant anemia, but their blood still doesn't carry

oxygen well enough to support the malarial parasite. So, they are

resistant to malaria while at the same time having little problem with the

hemoglobin mutation. However, those unfortunate individuals who end up

with a double mutation, known as a "homozygous" condition, have a

severe problem with their hemoglobin molecules crystallizing under low oxygen

tension. This crystallization effect dramatically distorts the red blood cells

and they no longer fit very well through small vessels in the body. Of

course, this means that organs and tissues supplied by these vessels become

starved for oxygen. This causes a very painful and debilitating condition

with significantly reduced life span.

Now,

there are several interesting observations to note. Most beneficial mutations

achieve their

benefits with just one or rarely two point mutations. Also, it is hard to

miss the fact that all of the functions gained, at least those listed here, were the result of a mutation that

interfered with a previously established function or specific interaction.

And, as we all know from a famous children's story, it is far easier to break than to create. The

reason is that there are so

many different ways to break something compared to the relatively few ways to make

something work. Why else couldn't all the King's men put Humpty Dumpty back together

again? (Back to Top)

Enzyme

Evolution

But,

how did such apparently complex enzymes, such as penicillinase, evolve? A

bacterium is not going to evolve the enzymatic penicillinase function with just

one or two point mutations to some target sequence because the penicillinase

function is not based on the loss or hindrance of a pre-existing function or

interaction. So, how could such a function evolve?

There are many

theories as to how the penicillinase enzyme must have evolved. However, when it comes

right down to it, no one has ever demonstrated the evolution of the

penicillinase enzyme in the lab. As previously noted, bacteria that

produce the penicillinase enzyme were always capable of producing this

enzyme or they obtained the code for this enzyme via a plasmid from another

bacterium who had this code already formed.11

Sometimes, a point mutation is required

to deregulate the production of penicillinase so that much greater quantities

are produced, rendering the bacterium (and its subsequence offspring) instantly

resistant to greater doses of penicillin. But, this change really has nothing to

do with explaining how the rather complex penicillinase function evolved.9

So, are there any documented reports of the evolution of a complex

enzymatic function comparable to that of the penicillinase function?

Michael

Behe, a professor of biochemistry at Lehigh University, says that,

“Molecular evolution is not based on scientific authority.

There is no publication in the scientific literature in prestigious

journals, specialty journals, or books that describe how molecular evolution of

any real, complex, biochemical system either did occur or even might have

occurred. There are assertions that

such evolution occurred, but absolutely none are supported by pertinent

experiments or calculations.†5

Others,

such as the well known evolutionary biologist Kenneth Miller, disagree. In

his 1999 book, Finding Darwin’s God,

one of Miller’s challenges of Behe’s position includes a 1982 research study

by professor Barry Hall, an evolutionary biologist from the University of

Rochester. In this study, Hall deleted a gene (lacZ gene) in a type of

bacteria (E. coli) that makes an

enzyme (ß-galactosidase).

This enzyme converts the sugar lactose into the sugars glucose and

galactose. The E.

coli then use glucose and galactose for energy.

Others,

such as the well known evolutionary biologist Kenneth Miller, disagree. In

his 1999 book, Finding Darwin’s God,

one of Miller’s challenges of Behe’s position includes a 1982 research study

by professor Barry Hall, an evolutionary biologist from the University of

Rochester. In this study, Hall deleted a gene (lacZ gene) in a type of

bacteria (E. coli) that makes an

enzyme (ß-galactosidase).

This enzyme converts the sugar lactose into the sugars glucose and

galactose. The E.

coli then use glucose and galactose for energy.

Without

this lactase enzyme one would think that these bacteria and their offspring

would not be able to utilize lactose. However,

what Hall found is that after a short time (just one generation) of exposure to

a lactose-enriched environment these bacteria modified a different gene with just one

point mutation so that it gained the ability to produce a new

lactase enzyme.12 Since the original enzyme was composed of a

fairly large tetramer (~1,000 amino acids for each subunit), it seemed like the

evolution of the lactase function might require a fair amount of enzymatic

complexity (fairly large number and specific arrangement of amino acid

residues). In other words, it might be rather difficult to come across

very many enzymes with lactase ability out of the vast numbers of potential

arrangments within sequence space. So, the demonstration of such

rapid evolution of a completely different hexametric lactase enzyme was quite a

stunning success for Hall. How did these amazing bacteria evolve a brand

new enzyme to do such an apparently complex task?

As

it turns out, these E. coli bacteria had something of a spare tire gene

that Hall called the "evolved ß-galactosidase gene" (ebgA).

Just one point mutation was all it took to give this spare tire gene the ability

to produce a protein with the beneficial lactase activity. Hall was of

course disappointed to find out that only one point mutation was enough to

"evolve" this beneficial lactase activity. So, he did a very

interesting thing. He deleted both the original lacZ genes as well as the

evolved ebgA gene in some rather large colonies of E. coli. Interestingly

enough, none of these doubly mutated bacteria nor their offspring never evolved any

other gene or DNA sequence into a functional lactase enzyme despite observation

for tens of thousands of generations.

Hall was mystified. He described

these bacteria as having, "limited evolutionary potential." 12

The interesting thing is that these same bacteria that were limited in their

ability to evolve the lactase function would easily have evolved resistance to

just about any antibiotic in just a few generations of sublethal exposure. Compared to antibiotic

resistance, the evolution of even a single-protein enzyme is quite a

different matter. We are starting to climb the ladder of increasing

functional complexity. (Back

to Top)

Limited

Evolutionary Potential

Now

I ask, what exactly was limiting the evolutionary potential of Hall's bacteria?

Does the theory of evolution explain such limits? If so, how are they

explained? The theory of evolution claims the power to create incredible

diversity via mindless processes if given enough time. Well, how much

time, on average, would it take for E. coli, without lacZ and ebgA, to

evolve the lactase function? Can this time be estimated, even roughly?

If so, upon what basis can it be estimated?

According

to Hall's own calculations, a function that required just two independent

(neutral) mutations would take around "100,000 years" to achieve in E.

coli.12 It seems as though Hall does not understand the

statistics of random walk very well or he would not have been surprised when he

did in fact isolate such a double mutant in just a few days. The estimated

time for fixation is what caused Hall to estimate a time of 100,000 years for

the crossing of a gap of just two neutral mutations. What Hall did not

realize is that stepwise fixation of each mutation (spread to all members of a

population) is not required for such a gap to be crossed. With populations

the size of Hall's E. coli colonies, such a double mutation would be

realized in at least one bacterium in the population in just one or two generations using random walk alone. (Back

to Top)

Growing

Neutral Gaps

So,

is the problem solved? Hardly. With each doubling of the neutral gap

between the current genetic real estate and a new potentially beneficial

function, the random walk increases by a factor of two. For example, a gap of 2

amino acid residue differences has only 400 different options to fill (20

potentially different residues in each position in a protein sequence). A population of one

billion bacteria would quickly distribute itself among all these 400 options in

very short order (given that these 400 options were all functionally neutral

with respect to each other). However, doubling the gap to 4 differences would

increase the number of options to 160,000. Doubling the gap again

to 8 differences would increase the number of options to 25.6 billion. A gap

of 16 would yield 655 million trillion (6.5e20). In such a case, each

bacterium in the population of one billion would be surrounded by a sea

of 655 billion non-beneficial options. The time required to traverse this gap, even for a population of one billion bacteria, would run into the trillions

of generations. Why? Because the time required for a mutation to hit

even one of the residues that form the gap runs into the hundreds of thousands

of generations, on average. In other words, each random walk step would

take hundreds of thousands of generations. So, finding one specific spot

out of 655 billion options would require 6.55e9 x 1e5 = ~ 1e14 or 100 trillion

generations.

This is because natural selection cannot

preferentially select for any sequence that doesn't provide an improved function

over what was already there to begin with. The only forces for change that can sort

through such non-beneficial sequences are random mutations. These random

mutations randomly search through sequence space with the use of either short or

long random steps. However, regardless of the size of the step/mutation,

the odds of success are not changed. Such a random walk takes a whole lot more time than a

non-random direct walk would take - exponentially more time. This simple little problem is what

messes things all up for evolution.

For

instance, consider that there are many bacterial functions that are far more

complex than the relatively simple single-protein based enzymatic-type functions

of lactase or nylonase. Many single protein enzymes are actually fairly

complex, don't get me wrong. They certainly are far more complex than the

function of antibiotic resistance that arises via an interfering mutation.

However,

their functions are still relatively simple when compared to other cellular

functions of higher complexity.

For example, there are about 10130

potential protein sequences 100 residues in length. Of these 10130 potential proteins, how many

would have a specific function? Well, it depends on the function. It

depends upon how specific the arrangement of residues needs to be. So, as

an example, lets pick one of the more specifically arranged functional protein

that requires about 100 residues to work - like cytochrome c. Some

scientists, like Yockey, have estimated anywhere between 1050 to 1090

different potential cytochrome c proteins exist in sequence space.15-17 To understand how

big these numbers are, consider that the total number of atoms in the visible

universe is only around 1080. So, one can see that 1090

different cytochrome c sequences is an absolutely huge number. The problem

is, this pile

of 1090 cytochrome c proteins is absolutely miniscule when compared to 10130,

which is the total number of different potential protein sequences 100aa

in length. For every one cytochrome c sequence there would be about 1040

non-cytochrome c sequences in sequence space.

And

yet, this ratio gets exponentially worse as the complexity of function

increases. For example, the function of bacterial motility involves the

interactions of many different proteins all working together at the same time -

over 20 different structural protein parts in specific arrangement totaling well

over 10,000aa that must be specifically coded for in correct sequence.

The question is, how many different arrangements of these amino acid residues would

produce a motility system (or how many arrangements of 10,000 letters

would produce a meaningful, much less beneficial, essay in English)? For

argument's sake, lets say that 102000 different motility

systems could be made with such a stretch of amino acids. Despite this

apparently astronomical number of different motility systems, 102000

is still a tiny fraction of 1013,010 - the minimum potential protein

sequence space at this level of complexity (10,000aa level). Each sequence

with a motility function would be surrounded by at least 1011,000

sequences without the motility function. In fact, the beneficial sequence

density at this level of complexity seems to be so miniscule that evolution is

powerless to evolve any function at such a level of complexity. There

simply are no observable examples of any such function evolving in real time

- not one example (i.e., a function that requires more than a few thousand

fairly specifically arranged residues).

Now,

there are a whole lot of stories about how such functions must have evolved.

These stories are exclusively based on the notion that sequence similarities of

portions of such systems to portions of sequences in other systems of function

must mean that they share a common evolutionary ancestor. Certainly the

similarities do seem to indicate a common origin of some kind. However, as Behe

has repeatedly pointed out, nobody has provided any detailed explanation as to

how evolutionary mechanisms of random mutation and function-based selection

could give rise to the functional differences at higher levels of minimum

functional complexity. The functional differences are what are important

here - not so much the similarities. How are these differences explained

by any non-deliberate process? Both deliberate and non-deliberate

processes can explain the similarities, but how well can non-deliberate

evolutionary forces explain the differences?

The problem is that there is

always more potential junk than non-junk at any given level of complexity. The real

problem though is that this junk pile grows exponentially, relative to the pile

of potentially beneficial sequences, with each step up the

ladder of functional complexity. (Back

to Top)

The

Junk Pile and The Ladder of

Functional Complexity

The

ladder of complexity limits the ability of evolution to evolve beyond its lowest

rungs where the most simple functions, such as antibiotic resistance, can be

found. The target mutations required to achieve antibiotic resistance are

extremely simple to get "right" because there are so many

"right" options. However, the evolution of specific enzymatic

functions, like the lactase function, are a lot harder to get "right"

because far fewer options are "right." Then again, even these

functions are relatively easy to get "right" compared to more complex

multipart functions, such as bacterial motility systems, where all the protein parts

work together at the same time in a specific 3-D orientation with each other.

So, as one moves up the ladder of functional complexity, the difficulty of

finding any sequence that does anything beneficial at such a level of complexity

becomes exponentially harder and harder to do until not even trillions upon

trillions of years are enough. (Back

to Top)

A

Construction Foreman Who Cannot Read

It

is all very much like a construction foreman who never learned how to read a

blueprint, but who intuitively knows what works when he sees it in action.

His workers are the ones that know how to read blueprints and follow

directions exactly. The workers

also copy parent blueprints to use as templates for each new house that is to be

built. However, although they are

extremely careful copyists, the workers make little mistakes every now an then.

These little mistakes may not result in any phenotypic change whatsoever,

but sometimes they translate into slight or even major variations among the

actual houses built (the phenotype). The

foreman then comes to inspect the completed houses and picks the one that is the

“best†given the particular needs of that house for that location and housing market.

The choice of the foreman is based only on current function.5,6

He knows only what works right now.

He has no imagination, memory, or vision for the future.

If there is a part of a house that he does not recognize as having

current beneficial overall function, he will not select to keep that house and

the offending part will be lost from future blueprint options. The foreman goes around saying,

“Keeping do-dads around that don’t work is expensive!â€Â

He will not maintain what he does not recognize as beneficial right now in hopes that sometime in

the future, with some potential change in the housing market/environment, it may

develop into something beneficial. Once

the selection for the best overall house is made by the foreman, the workers find the blueprint for this

house and use it as a template for the next building project.

It

is all very much like a construction foreman who never learned how to read a

blueprint, but who intuitively knows what works when he sees it in action.

His workers are the ones that know how to read blueprints and follow

directions exactly. The workers

also copy parent blueprints to use as templates for each new house that is to be

built. However, although they are

extremely careful copyists, the workers make little mistakes every now an then.

These little mistakes may not result in any phenotypic change whatsoever,

but sometimes they translate into slight or even major variations among the

actual houses built (the phenotype). The

foreman then comes to inspect the completed houses and picks the one that is the

“best†given the particular needs of that house for that location and housing market.

The choice of the foreman is based only on current function.5,6

He knows only what works right now.

He has no imagination, memory, or vision for the future.

If there is a part of a house that he does not recognize as having

current beneficial overall function, he will not select to keep that house and

the offending part will be lost from future blueprint options. The foreman goes around saying,

“Keeping do-dads around that don’t work is expensive!â€Â

He will not maintain what he does not recognize as beneficial right now in hopes that sometime in

the future, with some potential change in the housing market/environment, it may

develop into something beneficial. Once

the selection for the best overall house is made by the foreman, the workers find the blueprint for this

house and use it as a template for the next building project.

But

what happens if the housing market changes the next year?

What if certain changes would benefit the house in this new environment?

For example, what if there were a prolonged drought and wild fires became

a threat making houses with tile shingles more resistant to fire than houses

with wooden or asphalt shingles? Would

the foreman be able to make these beneficial changes?

Consider

the thought that languages and thus blueprints are arbitrary in that they use

arbitrary symbols to represent ideas. A

change or evolution of a symbol does not necessarily correlate to an equivalent

change in the attached idea. If a

symbol changes, even a little bit, the attached idea may simply disappear,

leaving the “new†symbol without any recognized function.

The symbol is now meaningless. For

example, what if the blueprint for our house in question called for “wooden

shingles.†Each of the words,

“wooden†and “shingles†is an arbitrary group of symbols that represents

an idea to an English speaking person. If

the blueprint could be changed to read “tile shinglesâ€Â, the understood

change in meaning and the resultant change in house building would be a clear

advantage in our fire-hazard environment. If

no pre-established alleles for “tile shingles†are available in the

blueprint pool of trait options, is there any way to create the “tile

allele†from anything that already exists in the gene pool?

The

problem for gradual change is that each letter change must make sense.

If “wood†is changed to “hoodâ€Â, the actual word “hood†has

meaning. However, is the meaning

for “hood†any closer to the meaning for “tile� Even

though hood has meaning, does it have beneficial meaning in this case? What

does “hood shingles†mean?

So,

not only does each word of the blueprint have to make sense to the workers, but

the combination or location of the words on the blueprint has to make sense as

well or else the workers cannot make anything, much less something

beneficial. Order is important at all

levels of complexity. Amino acid residue order is important for the proper

function of a single protein. Also, the order of multiple proteins is

important for the formation of a multiprotein system. Again, if the

workers build something that the foreman cannot recognize as beneficial right

now, it will be rejected. It is as simple as that.

In

order to better visualize the problem, put yourself in place of the foreman.

You can only select based on functions that work “right now.â€Â

With this in mind, consider the phrase, “Methinks it is like a

weasel.†6 Now, add,

subtract, or change one letter at a time from the phrase in any position or

order that you want. There are just

two more little rules to this game. Each

change that you make must make sense in English and each change must be

beneficial in a particular situation/environment.

See how far you can go and how much change in meaning you can get.

Changing the meaning very far is a lot more difficult than one might

think even if the beneficial nature of the change is not a concern.

Nature

runs into this same little problem. Changing genetic sequences too much destroys

all phenotypic function before any new function can be reached.

Maintaining a functional phenotypic trait along the path towards any

uniquely functional trait requires multiple changes (maybe even hundreds or

thousands at higher levels of functional complexity) that do not change the original function and do not achieve new

function, until all the changes are in place.5,12

This is because many functional genetic elements are isolated from each

other like islands on a large ocean of neutral function or even detrimental

function.

Consider the fact that most

character sequences of a given length have no

meaning to an English speaking person. The

same is true for sequences of DNA. The

vast majority of potential genes of a given length mean nothing to a given cell. Any

gene that happens to get mutated into one of these unrecognized or neutral genes

becomes suddenly lost in the ocean of neutrality where no guidance is

available. Without guidance,

evolution drowns in this ocean. (Back to Top)

Adding

a Stereo System to a Car

Some

say that evolution need not work like this but that the mindless processes of

nature evolve new traits and gene pools by simply adding on previously defined

genetic elements to an established system of function... like the addition of a

stereo system to a car. The addition of these units enhances the function

of the established system, even to the point of giving it new functions that it

never had before. In this way, a simple system of function can be enhanced

in complexity step by tiny step.

Let's

try a thought experiment to illustrate this point. Consider the sentence

in a large book of sentences that reads, "I am." Now add any

other word onto this sentence. The only rule is that whatever word you

choose must make sense in the context of the other sentences and the book as a

whole. For example, I could add the pre-formed word, "pleased"

and make the new sentence read, "I am pleased." This makes sense

in English and it adds meaning to the sentence (whether or not it makes sense to

the rest of the paragraph is another story). The new word,

"pleased" could have been the result of a duplication mutation of a

gene somewhere else that just happened to get inserted into our sentence.

But, if the mutation had read, "I am very", this phrase does not

necessarily make sense

in most situations/environments. The addition of the word "very"

probably destroyed the

previous function of our sentence without creating a new function.

However, if the phrase "I am pleased" was first to evolve, the phrase,

"I am very pleased" could evolve next and make sense.

With these

rules in mind, try and keep adding on words (or subtracting words) and see how

far you can get given a particular situation/environment. Maybe the next mutation could read, "I am very

pleased Tom." Then, "I am pleased Tom." Then, "I am

Tom." We could also go another route and say, "I am

very pleased in Tom." Then, "I am very pleased in seeing

Tom." Then "I am very pleased in seeing Tom run."

Then, "I am very pleased in seeing Tom run fast." Then, "I

am very pleased in seeing Tom run real fast." Then, etc. etc. etc.

We can evolve quite a few different phrases with quite a few unique meanings

with the simple addition or subtraction of previously defined words. Could

genes in DNA do the same thing? Technically yes, but there are just a few

problems to consider.

Remember

that not every defined word that exists in English will make sense when added to

the phrase, "I am." Granted, the odds that one will make

sense seem to be fairly good though. However, the longer our sentence

gets, the less words there are that make sense when they are added to our

sentence in the context of a specific situation/environment. Consider also that the placement of the words within our

sentence is extremely vital to the functionality of the sentence. I might

say, "I am green." This phrase makes sense in English. But

what if the word "green" had been inserted into the wrong place?

The sentence could just as easily have "evolved" to read, "I

agreenm." This makes no sense in English and destroys the function of

a previously functional sentence. Consider also that the duplication

mutation could have occurred or been inserted into an area of the book of

sentences where it was not needed. What are the odds that it would land in

exactly the right "evolving" sentence in exactly the right position

within that sentence when there are potentially millions of other locations it

could have landed? Then consider that the sentence itself, even if it

might make sense by itself, must make sense as it relates with the other

sentences around it and in the rest of the book. If any of these problems

arise, that sentence is lost in the ocean of non-beneficial function. (Back

to Top)

One

Last Question

If

the theory of

evolution runs into such apparently difficult statistical problems, how is it that

this theory can be so earnestly presented as the only

"rational" answer to the question of the origins of living things? (Back

to Top)

-

Lewin,

Benjamin, Genes V, Oxford

University Press, 1994.

-

Gelehrter,

Thomas D. et al. Principles of

Medical Genetics, 1998.

-

Callender,

L. A., Gregor Mendel: An opponent of descent with modification. History

of Science 26: 41-75. 1988.

-

Genetics

131: 245-253, 1992.

-

Behe,

Michael J. Darwin’s Black Box,

The Free Press, 1996.

-

Dawkins,

Richard. The Blind Watchmaker,

1987.

-

Mendel,

Gregor. Experiments in Plant Hybridization. 1865.

-

Veith,

Walter J. The

Genesis Conflict, The Amazing Discoveries Foundation, 1997, p.

82.

-

Carl

Wieland, Antibiotic Resistance in

Bacteria, Creation Ex Nihilo Technical Journal, 8:1 (1994), p. 5.

-

Felix

Konotey-Ahulu, The Sickle Cell Disease Patient (New York: Macmillan, 1991),

p. 106-108.

-

R.

McQuire, Eerie: human Arctic fossils

yield resistant bacteria, Medical Tribune, 12/29/1988, pp. 1, 23.

-

B.G.

Hall, Evolution on a Petri Dish. The

Evolved B-Galactosidase System as a Model for Studying Acquisitive Evolution

in the Laboratory, Evolutionary Biology, 15(1982): 85-150.

-

Dugaiczyk,

Achillies. Lecture Notes,

Biochemistry 110-A, University California Riverside, Fall 1999.

-

Ayala,

Francisco J.

Teleological Explanations in

Evolutionary Biology, Philosophy of Science, March, 1970, p. 3.

-

Yockey,

H.P., J Theor Biol, p. 91, 1981

-

Yockey,

H.P., "Information Theory and Molecular Biology", Cambridge

University Press, 1992

-

Sauer,

R.T. , James U Bowie, John F.R. Olson, and Wendall A. Lim, 1989,

'Proceedings of the National Academy of Science's USA 86, 2152-2156. and

1990, March 16, Science, 247; and, Olson and R.T. Sauer, 'Proteins:

Structure, Function and Genetics', 7:306 - 316, 1990.

(Back

to Top)

.

Home Page

. Truth,

the Scientific Method, and Evolution

.

Methinks

it is Like a Weasel

. The

Cat and the Hat - The Evolution of Code

.

Maquiziliducks

- The Language of Evolution

. Defining

Evolution

.

The

God of the Gaps

. Rube

Goldberg Machines

.

Evolving

the Irreducible

. Gregor

Mendel

.

Natural

Selection

. Computer

Evolution

.

The

Chicken or the Egg

. Antibiotic

Resistance

.

The

Immune System

. Pseudogenes

.

Genetic

Phylogeny

. Fossils

and DNA

.

DNA

Mutation Rates

. Donkeys,

Horses, Mules and Evolution

.

The

Fossil Record

. The

Geologic Column

.

Early Man

. The

Human Eye

.

Carbon

14 and Tree Ring Dating

. Radiometric

Dating

.

Amino Acid

Racemization Dating

. The

Steppingstone Problem

.

Quotes

from Scientists

. Ancient

Ice

.

Meaningful

Information

. The

Flagellum

.

Harlen Bretz

. Milankovitch

Cycles

Debates:

Stacking

the Deck

God

of the Gaps

The

Density of Beneficial Functions

All

Functions are Irreducibly Complex

Ladder

of Complexity

Chaos

and Complexity

Confusing

Chaos with Complexity

Evolving

Bacteria

Irreducible

Complexity

Scientific

Theory of Intelligent Design

A

Circle Within a Circle

Crop

Circles

Mindless

vs. Mindful

Single

Protein Functions

BCR/ABL

Chimeric Protein

Function

Flexibility

The

Limits of Functional Flexibility

Functions

based on Deregulation

Neandertal

DNA

Human/Chimp

phylogenies

Geology

The

Geologic Column

Fish

Fossils

Matters

of Faith

Evidence

of Things Unseen

The

Two Impossible Options

Links

to Design, Creation, and Evolution Websites

Since

June 1, 2002

The

theory of evolution proposes that all the various blueprints of living things

are descendents of a single common ancestor blueprint.

The diversity of blueprints that exist today is simply the result of

variations on a single theme. If

true, the power of the mindless evolutionary force of nature is truly

astounding. The sheer creativity

and magnificent diversity of nature is enough to make even the most cynical

stand in silent awe. If humankind

could harness this power and speed it up with the aid of our intelligent minds,

the implications for advancement seem unlimited.

The

theory of evolution proposes that all the various blueprints of living things

are descendents of a single common ancestor blueprint.

The diversity of blueprints that exist today is simply the result of

variations on a single theme. If

true, the power of the mindless evolutionary force of nature is truly

astounding. The sheer creativity

and magnificent diversity of nature is enough to make even the most cynical

stand in silent awe. If humankind

could harness this power and speed it up with the aid of our intelligent minds,

the implications for advancement seem unlimited.  Darwin

was unable to answer this question although the answer was in fact available in

his own day.

Darwin

was unable to answer this question although the answer was in fact available in

his own day. The

variation in allelic expression can be quite dramatic.

The

variation in allelic expression can be quite dramatic. Others,

such as the well known evolutionary biologist Kenneth Miller, disagree. In

his 1999 book, Finding Darwin’s God,

one of Miller’s challenges of Behe’s position includes a 1982 research study

by professor Barry Hall, an evolutionary biologist from the University of

Rochester. In this study, Hall deleted a gene (lacZ gene) in a type of

bacteria (E. coli) that makes an

enzyme (

Others,

such as the well known evolutionary biologist Kenneth Miller, disagree. In

his 1999 book, Finding Darwin’s God,

one of Miller’s challenges of Behe’s position includes a 1982 research study

by professor Barry Hall, an evolutionary biologist from the University of

Rochester. In this study, Hall deleted a gene (lacZ gene) in a type of

bacteria (E. coli) that makes an

enzyme ( It

is all very much like a construction foreman who never learned how to read a

blueprint, but who intuitively knows what works when he sees it in action.

It

is all very much like a construction foreman who never learned how to read a

blueprint, but who intuitively knows what works when he sees it in action.